The saying that “a picture paints a thousand words” was reportedly first used by Frederick R. Barnard in Printer’s Ink in December, 1921. Reading companions of Common Or Garden Theologian will know that the use of imagery is a very significant part of my method, but this post is a level up from the regular deployment of apposite images to act as foil and complement to the words. My subject here is one of the most famous pieces of world art: Hans Holbein the Younger’s ‘The Ambassadors’, completed in 1533, which is something of a constant muse of mine. Here are a few introductory remarks to explain. Much more will follow in further articles- too large a serving to offer all at once! This is to whet your appetites, or maybe to introduce you to what I propose is a cultural landmark in the development of our civilisation, in which (not least) the relationship between science and religion should be appreciated to be of central importance. In short, I suggest that The Ambassadors is not so much a key painting as it is a Key Text.

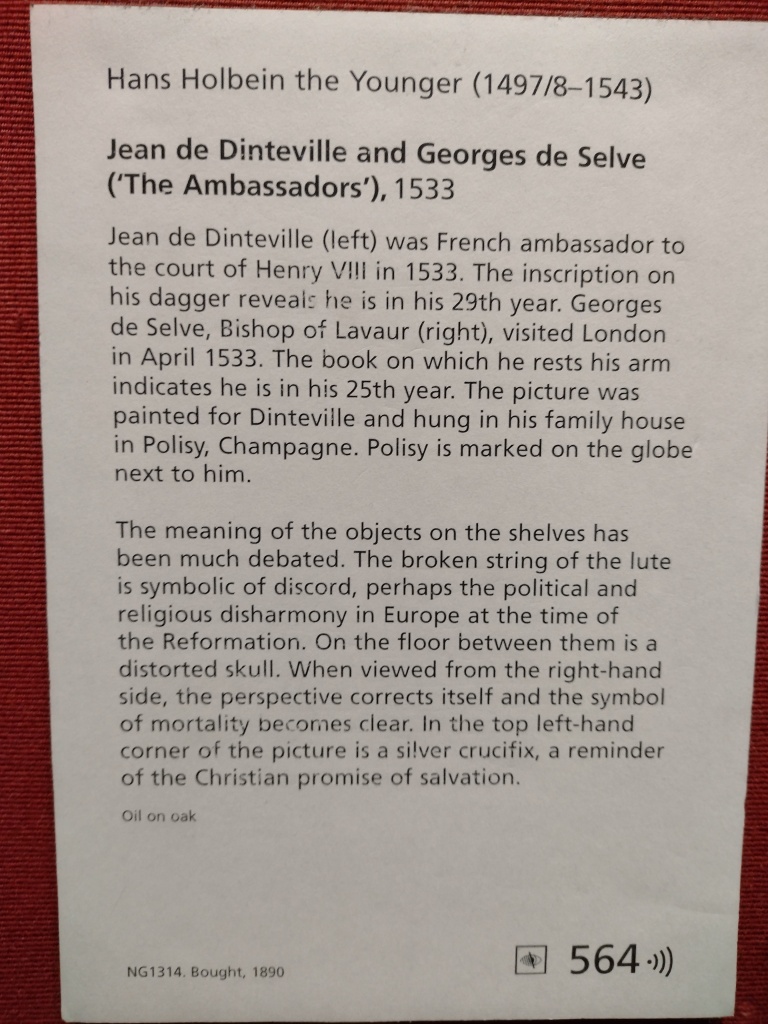

The initial sense of intrigue I felt in viewing this painting was considerably stimulated by John North’s 2002 book, The Ambassadors’ Secret, where he evidences over 350 pages that there is a great deal of hidden meaning to be discovered within Holbein’s early Renaissance painting. One might have supposed that Jean de Dinteville (a French ambassador, on the left, the commissioner of the painting) and George de Sevre (a senior Roman Catholic priest, on the right) are set against a backdrop of exotic bric-a-brac to create a more engaging scene- merely a means for the painter to show off his skill and artistry. Well, Holbein’s consummate creativity in depicting the full range of light and texture in both representation of objects and personal portraiture is certainly on spectacular display here. It seems Holbein can do with a brush what we moderns might imagine could only be achieved with a camera. But this painting is much more than a quick visit to the photobooth by two well-to-do guys on a business trip to London.

Jean de Dinteville commissioned his painting from the travelling German-Swiss master from Augsburg to memorialise his meeting and mission undertaken at the Pope’s behest with the soon-to-be Bishop Georges de Selve. These two young Catholic leaders were brought together in London because what had once been one was in the process of being split asunder. I say ‘Catholic’, which would have been left unsaid as a category until the early 1500s, because Henry VIII was in the process of turning England into something not Catholic- what we now call ‘Protestant’. This little idea of Protestantism ( a Dangerous Idea, says Alister McGrath) itself started in Germany, exported after its creation by Martin Luther, and had now reached the fertile mind of Henry Tudor, who it seems had realised its potential for solving his marital infertility problems. He had no (male) heir! The appeal of German Protestantism to the English clerics was rather different. An opportunity to cut loose from the theological apron strings of the dysfunctional Papacy was not to be sneered at, while they had no particular interest in sanctioning royal divorce. Younger readers may struggle to appreciate what a big deal divorce was just a generation ago, or how difficult it could be to remarry afterwards. In 1936 Edward VIII abdicated in these circumstances, a turn of events that underlines that the significance of Christian marriage between any two individuals continued to have societal ramifications four long centuries after two divorces and two beheadings at the will of King Henry VIII. From such social schisms in the nations of Europe it was feared that cosmic disaster would follow. Such hyperbole is warranted: some 50 000 to 70 000 souls came to a premature end under the reign of Henry, but the history books8 typically only mention his six wives. Heaven and earth would be split apart, to the general detriment of Christian society, and especially to the political reach and power of the Pope. So Pope Clement VII dispatched Jean de Dinteville on several diplomatic missions in an attempt to maintain the influence of Rome, and it was during his year long stay in London that he was briefly joined by Georges de Selve. But to no avail. King Henry, with his new Protestant clerics, achieved his desired divorce from Katherine of Aragon and then his subsequent marriage to his mistress, Anne Boleyn. The mission that the young ambassador and bishop had been charged with ended in abject failure.

There need be no harm or shame in this failure for the ambassador and his priestly companion. The failures, if failures they were, were surely the responsibility of the most senior parties, and not to be laid at the feet of Jean and Georges. Sometimes men strive against great odds, and against the machinations of greater authorities, yet find their striving to be in vain. But valiant none the less, no doubt. The friendships forged in such furnace are to be treasured and celebrated- and why not in such a grand painting?

But this is not that painting. That element is certainly present, yet there is much more. The two storied furniture, grandly adorned with a fine tapestry, is crammed with contemporary objects that do not fit the category of kitsch ornament. The most advanced instruments for accurate navigation are distributed across the upper stage- that is, instruments for knowing where one is, and how to get to where the merchant or traveller desires with safety and efficiency. If painted today, the upper level would likely show night vision binoculars, satellite navigation with GPS locator, and a maritime radar apparatus. On the lower shelf we see a sampling of cultural objects- musical instruments in the main, representing the best of the creative affairs of the most cultured persons- and books of ecclesiastical music and liturgy. Perhaps these items would still perform that representative function today. What we are shown then is a summary of the cutting edge understanding of the nature of European culture and its place in the cosmos, in particular, in its creative grasp of the world in all its most significant aspects. This is a summary of early Renaissance Humanism in the context of the established Church.

But it is most emphatically NOT the Renaissance Humanism as is commonly spoken of today: that species of human endeavour that travels inexorably away from established authorities and Traditions, especially those of Church, whether Catholic or otherwise, from God or gods of whatever flavour or kinds. This picture, presumably according to criteria set in dialogue between de Dinteville and Hans Holbein, stands as a theological and spiritual signpost against that mode of hubristic humanism. There are two or three principal signs of this fact. Firstly, the intricately patterned floor is closely modelled on the mosaic decoration found on the floor of Westminster Abbey, or, if you prefer, at the Sistine Chapel in Rome. Perhaps that is exactly the point: the two are the equivalent because there is One Church, that God will not allow mere mortals to sully or divide. Secondly, there is a curious and mysterious detail in the upper left corner of the painting behind the French Ambassador. Just visible to the attentive viewer is a crucifix. Behind everything that is transitory in this sumptuous and accomplished image is the Great Statement of God in the Christian Messiah: Christ came in our flesh and died for sinners. There will come a final reckoning, we are reminded, that will not be diverted by the crafty manipulations of either princes or paupers. As the crucified Christ is glimpsed from behind the green curtain, we might remember the words of James the apostle to men who seek to go about their business through the ages:

13Come now, you who say, “Today or tomorrow we will go into such and such a town and spend a year there and trade and make a profit”— 14yet you do not know what tomorrow will bring. What is your life? For you are a mist that appears for a little time and then vanishes. 15Instead you ought to say, “If the Lord wills, we will live and do this or that.”

James 5:13-15 ESV

Thirdly, and most obviously, there is the memento mori at the bottom of the picture, hovering rather than resting on the patterned pavement. It was a commonplace of art to feature skulls and the like, constantly reminding all alike of their passing mortality. But this skull is another tour de force of Holbein’s art- an anamorphic image, presenting the viewer with a distorted perspective that forces you to adopt a very different viewpoint in order to see it in its proper proportion and form. My own photo above shows the view from bottom left, on the floor- this does not work!

Rather, you have to go to the right of the picture and look down from the level of Georges de Delve’s shoulder. It seems this was the position a viewer would enjoy when passing down the stair next to the picture in the Polisy home of de Dinteville’s family.

In these ways I see the painting presenting us with a considerable number of strong claims and messages. Foremost amongst these are the following: the two men’s relationship stands in value and significance for all time, despite the passing successes and failures of their personal lives and occupations, even in the causes of Popes and Kings. By contrast, over all our temporal concerns is the sovereign Will of God expressed once for all in the sacrificial offering of God’s Son Jesus Christ, who can now be known as Lord and will surely be seen as such at the End of all things. And between these poles of value, sanctioned by Godself, is the creative place of humanity that walks in humility and grace as God decrees. It is possible for us to perceive the truth that we are like grass, dust and to be consigned to ashes- and yet, in the very grace of God, we can live creative and constructive lives of value as members of the community of faith, in which our mortality is ennobled by the greater truth of the Incarnation. Christ came to be one of us. Christ died, as we do; and truly, He rose again. And so we too may come to share in the Hope that triumphs over human futility.

Hans Holbein painted other portraits featuring the instruments of navigation seen in The Ambassadors, while some are backdropped by decorated and ornate fabrics. However, The Ambassadors is unique amongst his work that survives to our day: the entire rear boundary of the painted scene is concealed by the almost moving drapery of embroidered green fabric, shimmering with its silky sheen. We cannot see what is behind- is it a wall, or is it merely a dividing screen? I suspect the latter, as the scale of the mosaic floor indicates a greater distance to its rear edge than allowed by the shelving. All we can say is that the symbolism of the crucifixion, and therefore the Eucharist, is the only certainty of what lies behind all that we can see. For the perceiving viewer, as for Jean de Dinteville and Bishop Georges de Selve, the Lord Christ, who died, and lives forevermore, is the key to everything and eternity.

I hope you have been stimulated to think for yourself by Holbein’s painting; indeed, I think that is exactly what is intended. It is an aesthetic statement but also a facilitating experience. What is mankind, that You consider him? How much is by the design of commissioner and by artist? I cannot be sure, but I think we should credit both with a great deal. The letter of Second Corinthians speaks of Christian people as ambassadors of Christ, presenting the appeal of God to humans in all places and ages, and this role is not one of mere announcement. There is the full dignity of active agency in this outworking of the image of God. God is making his appeal through us, says the apostle Paul, and a key part of that appeal is the rich and creative humanity that can be realised by those who deliver that appeal, whether by creative preaching, by life witness in the era in which each of us finds our birth and life, and even in the skilful stroke of pigment-laden brush upon canvas.

Therefore, we are ambassadors for Christ, God making his appeal through us. We implore you on behalf of Christ, be reconciled to God. For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God.

2 Cor 5:20 ESV

© 2022 Stephen Thompson, except where credited.

Notes and references:

- 1 https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/a_picture_paints_a_thousand_words

- 2 A current google search for ‘100 top paintings’ shows The Ambassadors immediately features in the Top 30 images. Not everyone agrees, but for other examples: https://www.listchallenges.com/top-100-greatest-paintings-of-all-time/list/2 No 80. https://thepopularlist.com/most-famous-paintings-of-all-time/ No 64. Its a bit like being asked to choose your favourite child…

- 3 The Ambassadors, 1533, photographed by the author’s nearest and dearest in August 2022, 489 years after Holbein cleaned his brushes.

- 4 From the book blurb on John North’s The Ambassadors’ Secret: Holbein and the World of the Renaissance. {This} is a radical reinterpretation of one of the world’s most famous paintings. Holbein’s celebrated portrait of two French diplomats at the court of Henry VIII has usually been linked to the political and religious unrest of the day. John North shows that the painting has a very different, and previously undetected, central theme and many other meanings. Far from being random, the objects in The Ambassadors are deliberately, and very accurately, placed. In revealing exactly what they, and the painting, mean, The Ambassadors’ Secret opens a remarkable window on the world of the Renaissance.

- 5 You can access the file at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Ambassadors_%28Holbein%29 The National Gallery also has a webpage you can explore many details of this artwork.

- 6 Detail from The Ambassadors. The crucifix.

- 7 Christianity’s Dangerous Idea: The Protestant Revolution – A History from the Sixteenth Century to the Twenty-First Paperback – 18 Oct. 2007 by Alister McGrath (Author) My 2008 review of McGrath’s book is here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/customer-reviews/R2Q4CNO0W16X8W/ref=cm_cr_dp_d_rvw_ttl?ie=UTF8&ASIN=0281059683

- 8 https://www.historyextra.com/period/tudor/how-many-executions-was-henry-viii-responsible-for/

- 9 National Gallery commentary.

- 10 Author photograph of the skull from floor level (left side)

- 11 Newark Museum image of the anamorphic skull

- 12 Exploration of the floor pattern: http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/arth214/amb_floor.html

- 13 As you would expect, there is much more to the account of Jean de Dinteville’s role as ambassador than I have given in this introductory sketch. He continued to play an important part after the painting was completed, as you can read here: https://globemakers.com/jean_dinteville.html