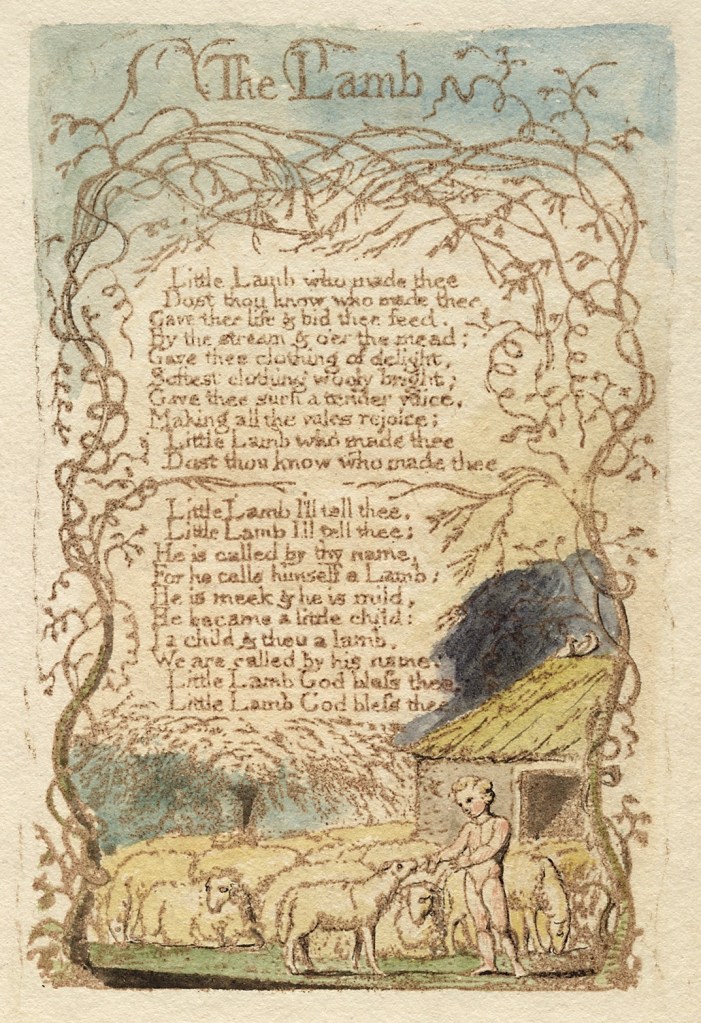

Some have described John Tavener’s ‘The Lamb’ as the perfect Christmas song. It is now the fortieth anniversary of this piece, first broadcast from Kings College Cambridge for Christmas in 1982, just months after he freshly wrote the most beautiful music for William Blake’s poem. (This is the 2014 recording.) The poem itself was written, and painted, in 1789, only just over 200 years previously. William Blake was popularly described as ‘mad’ by his contemporaries and even more recent commentators- a most unwarranted insult- though I have to say I do find his out-of-proportion distorted-limbed figures to be rather disturbing. Kinder critical appreciation now hails Blake as one of the foremost artists that Britain has ever produced. William Blake was voted 38th in the Top 100 Britons public poll in 2002, which reflects a level of appreciation far beyond that which he enjoyed in his lifetime. We Brits love a flawed romantic, and Blake was certainly that. It is said that he sent his last coin for a new pencil in order to sketch his beloved wife as she attended him at his deathbed.

Blake’s alleged ‘madness’ was really no medical or mental health matter. Rather, it seems he had a particularly keen eye for discerning the difference between good and bad religion, which is a sure fire way upset both authorities and traditionalists. Blake’s ‘Songs of Innocence’ were amongst his earliest artistic works as an adult, and his coming of age was sandwiched between what had we now call the American Revolution and what was about to become the French Revolution. So it was generally not a good idea to be seen to be upsetting the apple cart, whether in terms of spirituality, politics or civil rights. Blake was into all three. Sad as it was, we should not be surprised that he was so abused. As history often bears out, being in a minority, even a minority of one, doesn’t preclude being judged right in the long run.

Here is the third of Blake’s Songs of Innocence, in which his discerning faculties are profoundly in evidence:

Should we consider it surprising that Blake’s elegant poem had not been set to music before John Tavener adopted it as his lyric? In my view, it certainly qualifies as a hymn; far less luminous lines have been canonised in the hymnal. Perhaps it is the ambiguity of the first stanza that put off would-be song writers. The address is firstly to a farmyard sheep, made by a small boy who is asking undisguised philosophical questions, as small boys and girls are wont to do. Only in the resolution do we reach a point of more comfortable theological meditation. And that is why I love this text. Blake is engaging with the biggest of Big Questions, and when we dare to tackle such matters, we must cross boundaries and categories, thus blurring our pretence to objectivity. The youthful Blake is surely the child of whom his text speaks, and the undulled insight of the child is surely the basis of its power. True religion must be grounded in the personal appropriation of what God freely offers to us all. This is what upsets state religion, traditionalism and the overly intellectual approach that speaks only in abstractions and generalities. When the faceless civic leaders, bureaucrats and technocrats inevitably accuse us of taking our religion too seriously, the Nazarene Himself responds to each one with this question: “But who do you say I am?”

Which is what Blake’s child is doing in ‘The Lamb.’

Blake’s poem is a Sunday School lesson into the mystery of the Incarnation. And he achieves so much in 113 words! While avoiding explicit mention of the grown up terms – the Divinity and humanity of Christ, hypostatic union, and so on – Blake also includes the mystery of humanity compared with the animal nature of the young sheep. Here is a guided meditation for children on the whole Creation and its ultimate purpose. How are animals made? This is the first question. From the stuff of the world- the light and water and air of the fields and valleys in which life has its being. The boy is quite like the sheep in this respect, emphasised in Blake’s own illustration by his nakedness. He also has the advantage of enjoying the blessing of clothing and meat that sustains his mortal life as a human person. We accept that the boy knows that he is the offspring of his parents, and he knows too that the life cycle of the flock is maintained by the care and attention of the shepherds.

As the second verse begins, we see through Blake’s eyes that the young farmhand knows more than this. Not only can he deconstruct the ecological network of which man, animal, plant and land are constituted, he can discover behind all this what the grass-chewing creature is insensible to. How were we both made? he next asks. In the poem, the question is put directly to the sheep by the boy, because the boy already knows. He doesn’t need to ask himself. Yet he knows, I think, that his knowledge is incomplete, which is why he is talking to a sheep, that can only bleat; as the poem has it, with ‘a tender voice.’

The boy shares his profound enlightenment with us, as he attempts to instruct the little lamb which cannot appreciate the tender sounds he speaks. I read that sheep are not so stupid, and like dogs can recognise their given names, but there is a chasm from there to the scriptural use of ‘Lamb’ as metaphorical imagery for the person of Christ. Now here is the rich genius of Blake’s insight. Having set up the questions in the first stanza, Blake now plays with the identities of child and creature, Christ and Lamb, moving us back and forth between their various combinations. The boy is indeed like the little sheep, and yet utterly different. The Christ-child is first known as a baby, which the little boy himself was so recently. Yet the One the gospels call Christ is fearsomely different to us all. And at once, we need not be afraid, as the lamb is not afraid of the gentle boy, for baby Jesus is meek and mild, Blake here quoting Charles Wesley’s 1742 hymn. This is how William Blake paints the Incarnation- words to page and paint to paper. Most engagingly, that the Divine Christ makes Godself like a lamb! Blake makes us consider deeply the meaning in the metaphor: the Lamb of God, that oft quoted religious language of the lectern reading, means that God in Christ made himself like a bleating sheep, that more-or-less unquestioningly follows the simple shepherd from one field and pasture to another, before being offered up for shearing and, finally, slaughter.

Then the order is reversed: I a child & thou a lamb.

The interchange is broken to recall that difference is as determinative of meaning as similarity. Life is different to non-life. Humanity is different to creatureliness. Divinity is different from humanity. And here is the Claim: God in Christ Jesus, the Christ Child of Christmas bridges the Great gulf between the immaterial, which God must be, and the material, which is where our senses place us. What could a mere munching sheep have to do with a boyish man, or any human person, with the Transcendent God?

We are called by his name.

In this line, Blake brings all three to unity. In the Creation Purpose of God, and in the particular metaphor of the Lamb of God, we find the confluence of God’s grace in creation, as matter and creature and man and God’s own Self come together, and so the boundaries between what was properly separated are meaningfully blurred. So Light dawns upon all of God’s creation, and the face of God comes into perfect focus, and we are Blessed.

So much of the beauty of this composition in word and picture is captured by John Tavener’s spine-tingling music. He sets the poem’s questioning introduction in a simple and childhood-evoking G major, before disquieting us with a dissonant chord of A minor with an added ninth note. In the repetitions (just like the themes of the poem) the melodic lines are inverted and/or reversed, as you can see in this guide. The dissonances and inversions resolve into the E aeolian of the four part chorale, the four voices mirroring the various ingredients of the poetic mediation. As if all that creativity is not enough, Tavener recounts that he wrote this piece in just a quarter of an hour and dedicated it as a gift for his nephew’s third birthday, further evoking the innocent little boy of Blake’s poem.

A perfect carol for Christmas? I think so.

I relish the wide variety of music that is featured in the annual services of carols from Kings. The surprise is always part of the fun! But the readings are a constant, and the centrepiece for me is the first chapter of John’s gospel, introduced on this wise: “St John unfolds the great mystery of the incarnation.” There is so much to savour in that passage, itself a reflection on the Creation of Genesis 1 that the first Christians appropriated and integrated into their understanding of Who the had seen Jesus to be. Following his prologue, St. John collates and coordinates the multifaceted account of Jesus the Messiah as the Incarnation of God, beginning not with the nativity but with the crying out of John the Baptiser in the wilderness. ‘Prepare yourselves for Him, whose sandals I am not worthy to untie!’ The one announced as the coming Lord is at conclusion seen by St John as the One who speaks from the cross, gently charging him with the personal care of his mother, Mary, who had given birth to the son of God now giving His life before them both. The Great God of all things, Present and intimate with His people. In between are so many encounters, each recounted in the gospels to give us an authentic and reliable picture of Jesus the Messiah in which we might also encounter Him. It is in the juxtaposition of the multitude of testimonies that we come to behold His Fulness.

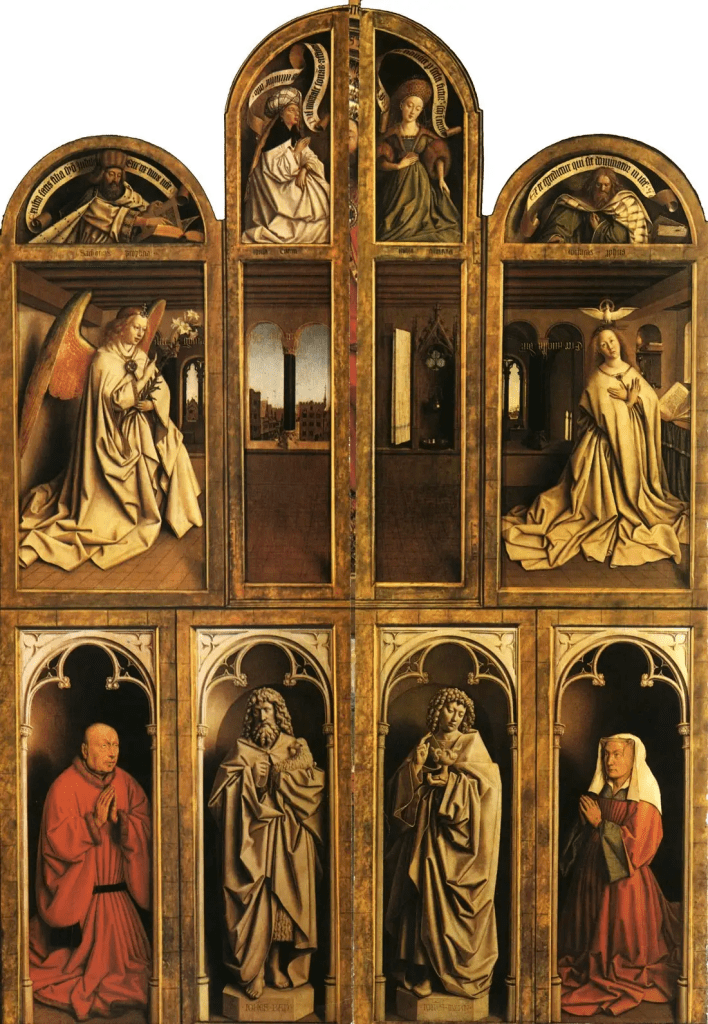

I don’t know how many people could read and write in Ghent, Belgium, in 1432, but we can safely assume not too many. Before printing, even those who could do both would have had limited access to books of any kind, and that included the Latin Bible. The people heard this read aloud in services, and doubtless remembered much of these excerpts. Church buildings across Europe before the Reformation were typically covered with educative paintings, as I have featured previously in this blog. In addition, further artworks adorned the altars of the grand churches, such as this polyptych altarpiece in St Bavo’s Cathedral. The ‘Ghent Altarpiece’ was commissioned from the brothers Hubert and Jan van Eyck, taking them 12 years to complete. Experts consider it (or them as there are 24 scenes!) “the first major oil painting,” perhaps therefore marking the transition from Middle Age to Renaissance art.

Such altarpieces were explanatory visual texts to the liturgy, a handy summary of the gospel message and a guide to the viewers’ place in the world, at least in the religious formulation of those who commissioned the works, and of the artists who catered to their tastes. If, indeed, you could not read, then the closed altarpiece at St Bavo’s gives a vital three-level summary of the theological cosmos; heavenly creatures, saints and glorified prophets at the top, earthly authorities, including the local lord and lady (Joost Vijdt and his wife Lysbette Borluut) who gave the commission at the bottom, and the meeting of heaven and earth in between the two levels. In the annunciation, the now permanently visible Angel Gabriel greets the ever-submissive and pietistic Virgin with the covenant invitation from heaven, which she accepts, and we see the hovering Spirit-dove of the Holy Ghost overshadowing Mary, imparting the Divine Seed. So the Incarnation is depicted at the centre of the cosmos, the centre of history and at the centre of daily life in this place. Of all the images on the altarpiece, the four which form the panorama of the Annunciation are the set which give, in the background to the figures of the archangel and the young woman, the most realistic setting. This could be a well-to-do house in Ghent. And in such a setting comes the Word of the Lord, and the Spirit’s impartation.

Perhaps at times other than during services, the altarpiece was opened in both directions to reveal a double row of images. They cut across time and the dimensions of reality, and all are more stylised than the annunciation. In the centre at the top we have a timeless vision of a heavenly state in which the figures of Mary and John the Baptist, key persons in the introduction to the nativity and Gospel, are flanking the Divine Person, vindicated in their faith in God. Is the central image of God the Father or of God the Son? The experts cannot agree, calling this enthroned figure ‘The Almighty God’ to hide their lack of discernment. As the figuration of YHWH God from the Old Testament transforms into that of the Trinity in the New Testament, our understanding of the revealed Person of God is progressively modified, and as I have already intimated, our ability to grasp the implications of the Incarnation is limited. Which is why the introduction to the reading of the gospel of John at Christmas speaks of mystery. All the Members of the Trinity are worshipped and adored, says the Creed, and this is emphasised in the upper row by the worshipping angels shown to the left and right of the Deity, Mary and John the Baptiser. Our current uncertainty about the seated Divinity can be taken to reflect the theological ambiguity of the Incarnation. I and my Father are One (John 10:30) said Jesus, so we are supposed to consider them in the same imaginative breath. The triptych of God, the ‘mother of God’ and the ‘greatest prophet’ could be a pointer to the divinisation of humanity and the creation of the single Body of Christ, but I may be reading too much into this. At the sides are the naked figures of Adam and Eve, concealing themselves in shame (in contrast to the young boy in Blake’s illustrated text). These two are the base reason that the Incarnation is necessary, and they as the disobedient couple are contrasted with the obedient Mary and John the Baptist that are now comfortably seated at the right and left of God our Redeemer.

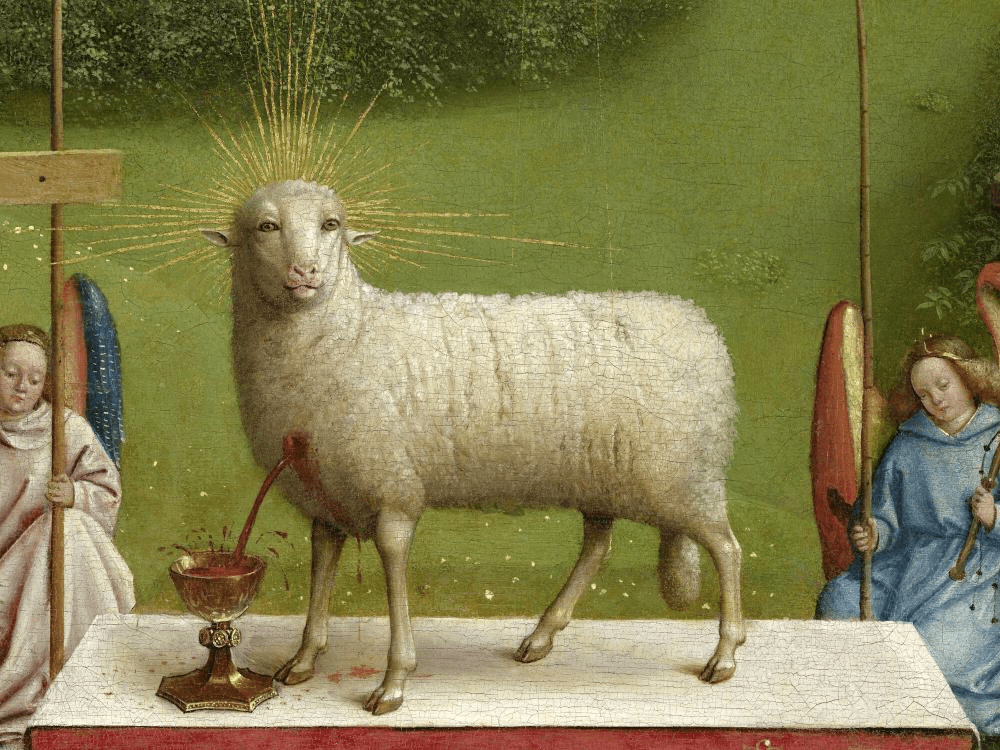

Below this nexus of scenes from the past and the present – or should that be the timeless now-but-not-yet present?- is an extended scene across five panels. The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb is displayed, and several groups of persons are depicted around about the central altar. The scene is somewhat like the final judgement, in a hereafter time, placed in an idealised landscape, rather than a Church or realistic setting. The vision of the Lamb from the book of Revelation is brought forward to the present; or we are transported there, while we gaze at the picture. There are clergy and soldiers, pagans and sinners and the pietistic worshippers- unfortunately separated by gender- visible angels and the hovering Spirit all gathered around. Behold the Lamb of God! This image combines the viewers’ current experience of the Eucharist, in which the bread and wine are lifted up to their gaze; and at the same time, we are drawn forward in time to the final revelation of the Lamb of God at the end of all things, where we will be gathered by God in judgement in the light of the Salvation Work of Christ the Lamb.

In this complex altarpiece we are engaged by a sophisticated theological construction. The many images function together to evoke a larger whole. A multifaceted picturing of spiritual realities is presented to us, from different times and spaces, dimensions and though various modes of depiction. As our gaze shifts from one to another, and we allow our meditation to be stimulated, the various combinations synergise to enlighten the eyes of our hearts. The painting itself reaches out to us, for example, in the way that the prophet Micah (top right on the front of the closed panels) places his hand on the picture frame, blurring this boundary between him and us. We and they may really be connected, if we have faith for this. The paintings work rather as the successive lines in Blake’s poem, drawing us back and forth as we struggle in faith with the God whose blessing we desire, as did Jacob with God’s angel. There is even a possibility that there was a music box and automated opening mechanism attached to the side panels at some period, adding further engagement to the experience.

Right in the centre, and right above the physical altar in the cathedral where the altarpiece has remained installed, is the figure of the Lamb of God. Here the brothers have left the most extraordinary insight. The shorthand is that Jan van Eyck was the painter, while Hubert his brother planned the overall scheme, but we cannot know who contributed what. So here is another mysterious pairing of characters that resonates with a theme in this study. Now the close up view below is what the modern viewer will see today, as a great deal of effort has been put into the recent restoration of the whole altarpiece, and of this panel in particular. You will be disturbed by this, because we are not now looking at the face of a regular sheep.

We now know that sometime after its original composition, the decision was made to ‘correct’ the work of the van Eycks. What should look like a lamb needs to look like a lamb. So they got in new artists and painted over the head to make it look like a proper sheep. You can see this in the images below.

Here on the left is the sheep’s head after exploratory cleaning in the 1950s; now there are four ears! But the eyes are still where they should be for a sheep- on the side of its head, as is proper for a herbivorous animal that is prey to a wolf or other predator. Using X rays and the like it has become possible to discover exactly what oil paint was originally applied in the fifteenth century and what was put on afterwards.

The ‘improved’ painting was disturbing enough, with the gushing spout of blood pouring forth into the eucharistic chalice. But as disturbing as the sight of the original face of the Lamb as Jan van Eyck left it? Instead of William Blake’s question, Dost thou know who made thee? we have a different question: Do you know what and Who I Am? It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the Living God (says Heb 10:31) and there is a good dose of holy fear portrayed in this image.

Were the ‘improvers’ right? If the word of God says Lamb then we should have a lamb, shouldn’t we? This question gets to the core of what the revelation of Scripture is all about. How can simple human words (yes, even the clever ones like incarnation and hypostasis) actually convey the Nature of God to human creatures with any accuracy? The best that we can hope for is through the use of analogy, metaphor and simile. Now similes are used in the Bible, but not often about God directly. Rev 1:14 gives three at once when describing Jesus’ appearance: “His head and hair were white like wool, as white a snow, and his eyes were like burning fire.” Metaphors are much more frequent: Psalm 18:2 The Lord is my rock, my fortress and my deliverer; my God is my rock, in whom I take refuge, my shield and the horn of my salvation, my stronghold. There is an encyclopaedia of metaphors for Jesus: The Light of the World, the Bread of Life, the Gate for the Sheep, The Shepherd of the Sheep, and, continuing the prophecy of Is 53:7, the Lamb of God. Such metaphors might be more or less distinguished from ‘titles’, ‘names’ and other descriptors.

Then there is analogy, for which a modern example is the three states of water standing for the Trinity. H2O is a liquid at room temperature, with certain properties somewhat in keeping with being in the liquid state. But lower the temperature below 0 degrees Celsius and those properties change dramatically. Yet it is the very same substance. Again, above the boiling point, the properties of the vapour are quite different. All the while the chemistry of the substance stays fixed. The same substance, with different behaviours. By analogy therefore: Same God, with one nature, yet a Trinity of different expressions. But steam and puddles and ice don’t generally co-exist in the same space, so the analogy breaks down.

There is much to dwell on here, and God’s intention is surely that we do meet with Him in the spiritual encounter that these literary devices make possible. That intention is mirrored on our side by the refining of the Creeds, where our forebears have concentrated as much accurate meaning into the confessions as humanly possible.

But we must admit that our metaphors are never going to be complete descriptions. How could human words sum up God?! If they could, we wouldn’t be talking about much of a ‘God.’ The Bible does have lots of metaphors for God, and especially for Jesus, because any one metaphor is apt in some respects but ultimately imprecise. We tend to push them too far, and commit the venal literary sin of mixing our metaphors when we try to compensate. The revelation of God enlightens us to deep truths that consign unbearable weight to the best words we have. The metaphor breaks.

We need not despair, because God is graceful and accommodates to us and to our language. God gave instruction to Moses about how to mend relationship with God. At the tabernacle lambs were brought for inspection and ritual slaughter. What had this to do with making propitiation to God for ‘the breakages we make in relationships’ otherwise known as sins? Quite clearly, absolutely nothing at all, except that God says it does. God decreed that the split blood of lambs (and bulls and pigeons) would be the acceptable price for spiritual redemption, and that decree was what made it so. John the Baptist declares, Behold the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world right after the Christmas prologue reading at John 1:29 (and again at v36). So Jesus picks up where the laws and institutions of Exodus and Leviticus leave off, putting human flesh on the metaphor. Now this makes a lot more sense, as unlike the brute animal, this Lamb knows what the potential sacrifice is intended to atone for, has freedom to decide whether to make the exchange, and complete agency to commit the deed. Now we are comparing apples with apples, I might say… to use an analogy.

So Jesus said to them, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you.

John 6:53 ESV

I have explained that our language breaks down as it is not fully up to the task of carrying all the meaning we want to convey. God is happy to be complicit in this with us. Jesus as the Lamb picks up the theological baton from the Tabernacle and Temple and makes the sacrificial offering personal. As I said to begin with, this is necessary, and it upsets the apple cart. The original hearers of the John 6 dialogue would not have grasped the foreshadowing of the symbolism of the Eucharist, but this was understood by the time the gospel was being committed to paper. At the time, the crowds who heard these words left him. It’s too difficult, they said. We would go too, said the Twelve, but we’ve nowhere else to go. It was simply their decision to keep their side of the covenant commitment with Jesus that made the crucial difference. Yes, this was the only difference, which is exactly equivalent to God saying that the sacrificial system would suffice – at least temporarily. The metaphors must break; the words will lose their function to symbolise, to communicate, to signpost relational Encounter. It takes a strong Word to resist such breakages under load. This is a general difference between the Spirit-inspired Word of God and our creaturely words, but in terms of the inscripturated word, both are alike; it is in the Will of God to determine what covenant exchanges will be honoured, and this is one of them.

It is plain to me that the van Eycks realise the problem of metaphor collapse as they plan the painting of The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb. There is more literal signification in the visual depiction of the sheep than there is in the phrase ‘Lamb of God.’ When we read that, we know it is speaking of Christ, God in human form. The symbolism of the lamb and the identities of humanity and divinity sit together satisfactorily in the oral form. How to get over this deficiency of representation? Perhaps you don’t. One should heed the Exodus 20 commandments and stick to the Jewish habit of avoiding imagery of the divine. But van Eyck comes up with a different solution. He creates a visual chimera of the creature and the God-become-Man. Following John the Baptiser (who we saw on the front of the altarpiece, remember) we are now familiar with the gospel claim that Jesus actually is the Lamb of God whom God the Father will recognise as the once-for-all sacrifice for ALL the sin of the world. Jan van Eyck paints a sheep-saviour. The human-like eye position speaks not of the aggressive predator but of the spiritual and relational purpose. The anthropomorphised God is now melded with the impersonal (sub-human) animal sacrifice. The true identity of Christ spills out in the painting- and in his double eyeline we are confronted, challenged, and invited to encounter. And even perhaps to consummation.

My speculation is that if William Blake had travelled to St Bavo’s in Ghent, he would have been as shocked as the rest of us, but would have strongly approved. He had his own artistic reasons for drafting figures with oddly proportioned limbs, while van Eyck’s distortion of the face of the Lamb of God is an even bolder move to accomplish an aesthetic end that conveys profound meaning. John Tavener makes musically equivalent moves in The Lamb, including the dissonant chord of A minor with an added ninth, and in refusing to give any time signatures in the score. The words should guide the pulse, he says, not the other way around.

The words we humans use have sufficient impact and import for most occasions, and we might augment their meaning through setting them to music. We make and break our vows with our words, and God hears both. Through metaphors and the like we can create poetry that may draw heaven and earth together. God’s Logos words (the Greek terminology of John 1) can be spoken in our tongues- much aided through Bible translation- but are ultimately much more powerful, creating worlds at His command. God decrees that His Word will not return to Him void, or empty of meaning. (Is 55:11) The genesis words of God created poets and painters and all humanity. Most wondrously of all, the Living and Active Words of God create Salvation. (Heb 4:12)

© 2022 Stephen Thompson

Notes and references for further study. The majority of direct sources are hyperlinked in the text but are not repeated in this list.

- The title of this post partly evokes this charismatic lyric, which I further modified: ‘You are the Words and the Music… You are the Song that I sing.’ Lyric and music by Doug Moody 1984.

- William Blake, 1789. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Lamb_%28poem%29

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/100_Greatest_Britons

- Resources for school students can before found here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zdjw7p3/revision/5 AND https://www.studocu.com/en-us/document/studocu-university/studocu-summary-library-en/william-blake-songs-of-innocence-and-experience-summary-and-analysis-the-lamb/1051273 AND https://mrsjgibbs.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/blake-poems-explained.pdf The BBC page says that The Lamb was written in 1979 but this is not correct. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Lamb_(Tavener)

- There is a growing summary of the range of critical opinion and appreciation of Blake here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Blake Accessed 27 12 22

- John Tavener: The Lamb – The Erebus Ensemble [live] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jp1Eq4nfnKc I agree with others who comment that the clarity of diction as well as the quality of the recording make this a stand-out version.

- If you are curious, here is an annotated score which highlights the technical details of this stunning composition. It plays in real time while the singers perform. The Lamb (Tavener) Motivic Development analysis https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DqZYA9EU6PI

- Jan Van Eyck, 1432 Ghent Altarpiece. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20200201-is-this-the-first-view-of-god-the-father-in-art

- See https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/27/arts/design/mystic-lamb-ghent-altarpiece-van-eyck.html for the spectacular sight that greeted worshippers.

- See also: https://www.artfixdaily.com/news_feed/2020/08/20/6196-you-can-now-get-an-even-closer-look-at-the-ghent-altarpieces-rest AND https://artinflanders.be/en/artwork/ghent-altarpiece-adoration-mystic-lamb-detail-8

- Agnus Dei, by Francisco de Zurbarán. 38 cm × 62 cm. Oil on canvas. Museo del Prado, Madrid https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agnus_Dei_%28Zurbar%C3%A1n%29#/media/File:Francisco_de_Zurbar%C3%A1n_006.jpg