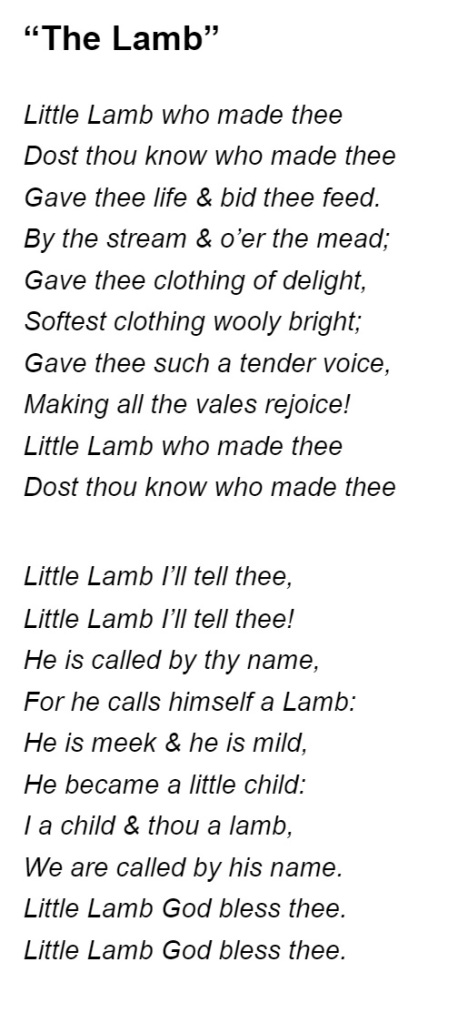

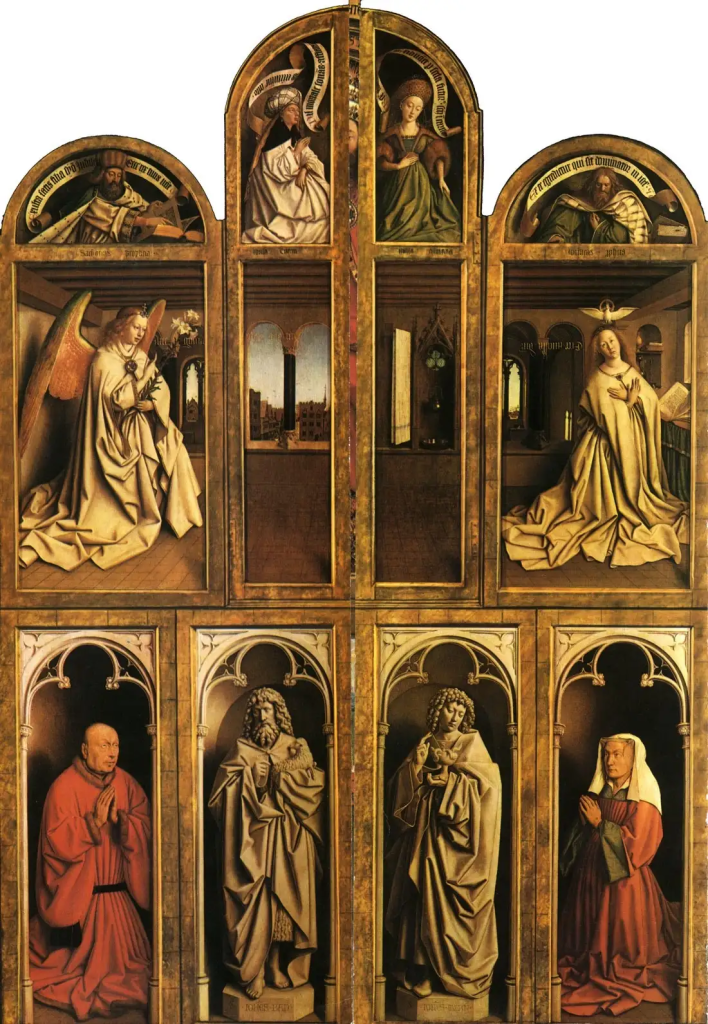

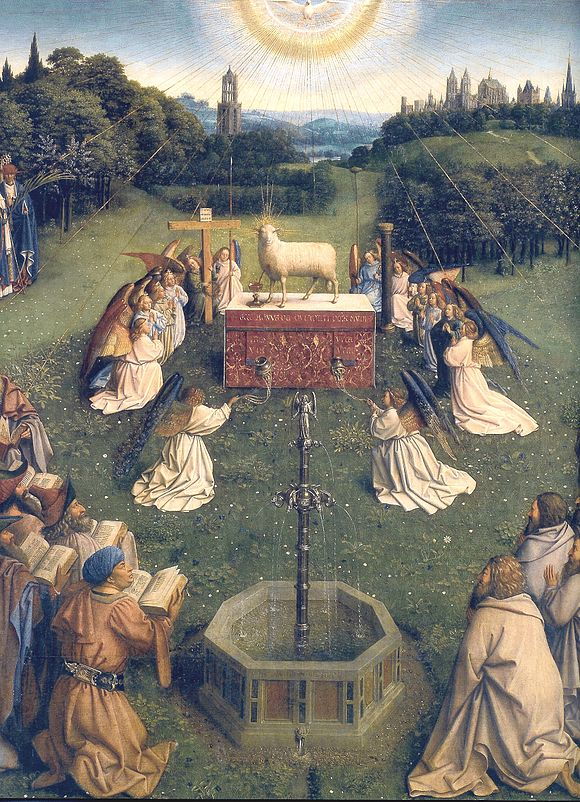

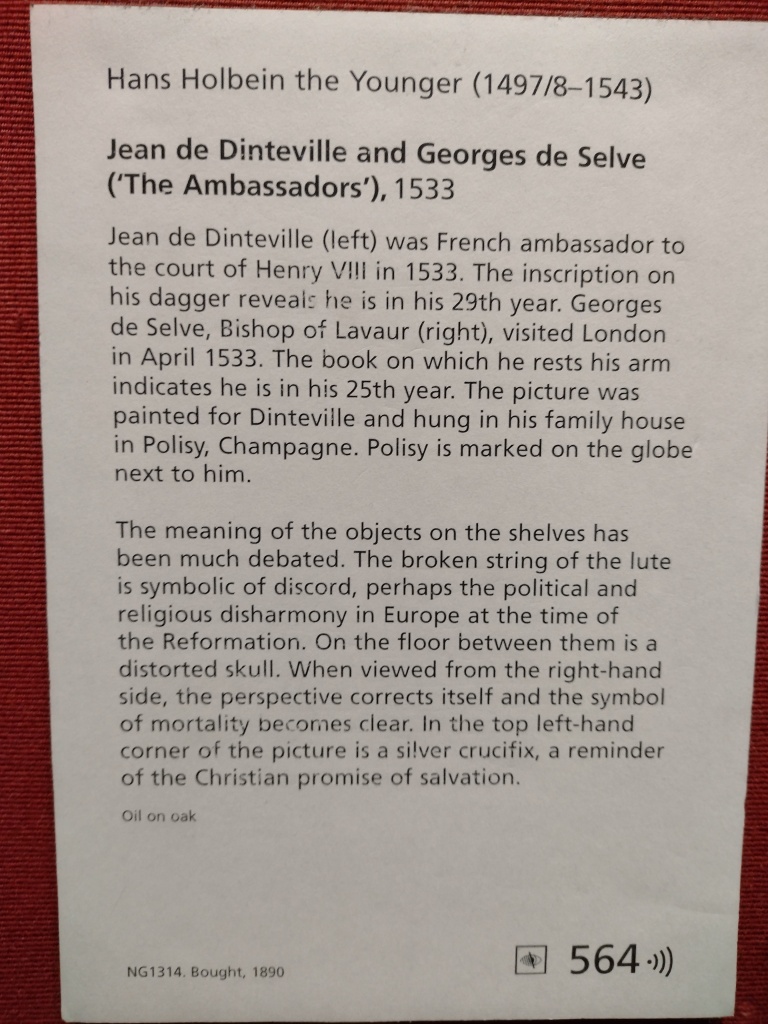

My intention has been to reflect on Creation theologically, in an holistic and integrative manner. So there is more to my writing at common or garden theologian than simply a theology of Creation, though that is undoubtedly its principal focus. I have attempted to be creative in my theologising about Creation, and this is being expressed in creative prose, reflective as well as analytical writing, through personal as well as objective considerations, and even some poetry. I celebrate a great deal of visual creativity, through photographs and art, drawing these seamlessly into the description and argument I am attempting in the text. I’ve made some art of my own, often by jumping off from (significant) pieces by others- even including Michelangelo. This all underlines and explicates* one of my principal claims: I say that God wants us to create the future with Godself, to be co-creators of God’s future. I call as evidence that my presentation in this blog is necessarily co-creative, for it can only be authentic in that mode. [Having said that, you will allow me to say that it is immaterial whether you think my attempts at ‘art’ are any good, or whether you like it or not.]

*explicate: to analyse and develop, discovering meaning.

This post is (another) attempt to distil my findings, lessons and conclusions into an encyclopaedia-style summary; to objectify my claims into statements. This is important, as I want my readers to be able to gain clear and succinct answers to questions like, “What are you really saying?” “Can you sum up your ideas for me please?” and so on. I am happy to oblige, as I’d rather like to read that myself. But at the off it needs to be made clear that this summary is a reductionist project. I am now happy to assert that I have revelled in the journey at commonorgardentheologian.co.uk, and its partner site for science teachers who are interested in specifically Christian perspectives on science and religion. It has been a very stimulating, rewarding and satisfying journey-process, mostly because I have been able to express many of my creative interests all in the same place. Make no mistake: this summary may well enlighten your understanding and assist your own reflections on Creation, as a Judeo-Christian category as well as more widely, but it is not possible to encapsulate all that has been achieved… produced… Created in this journey of forty seven chapters, and counting… in an objective summary. Substance will be lost, by definition! May I gently suggest that this lesson might be explicated like this: it is in my extended reflections on the Book of Genesis and the theme of Creation in the scriptures overall that my reflections have become alive. In a small way I said this in the post, ‘Which comes first: the wine or the wineskin?’ Or as some of my preaching friends like to repeat, ‘The journey is the destination.’ If I am right (and perhaps this is really not that controversial) then the most important thing to grasp about cocreation is to do it; to be a cocreator! The undiscovered, or, better perhaps, the ungrasped truth is that as God is inviting us all to go this way, we should ‘Come and see…’, ‘Come and be…’ and, ‘Come and do.’

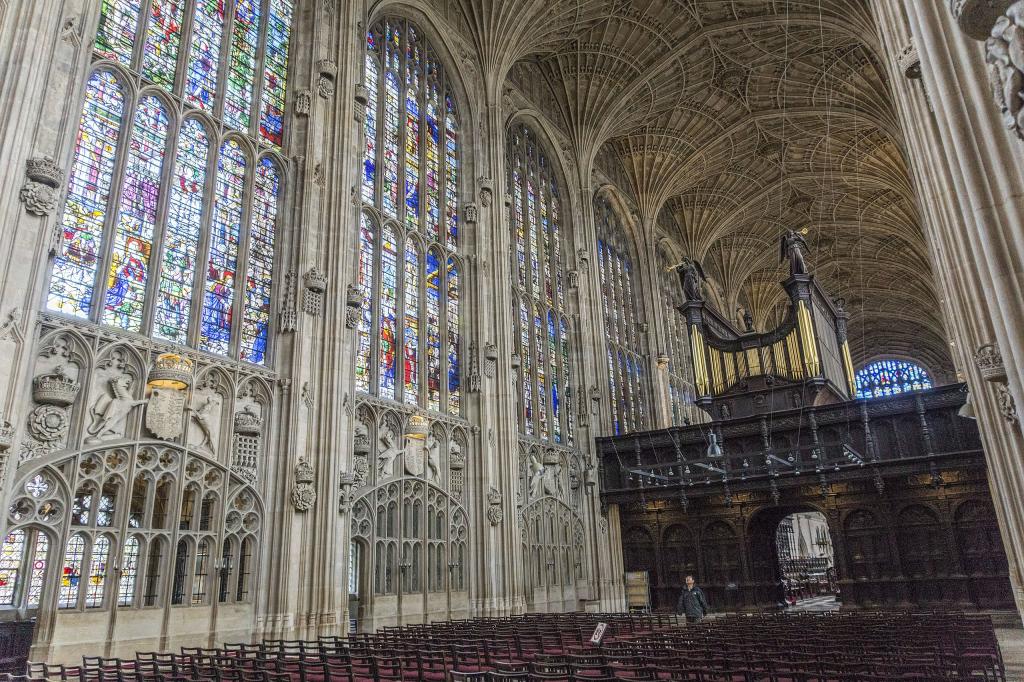

I am writing this on Boxing Day 2022, having listened to another performance of Nine Lessons and Carols as is my habit in the Christmas season. At the conclusion of this recording is a 1991 documentary about the choristers who sing at the Kings College chapel, in which one member observes that Stephen Cleobury, their director of music from 1982 to 2019, took great pains to ensure that all the training and intensely rehearsed singing didn’t cause a loss of authenticity in merely beautiful concert performances. The choir exists by Henry VI’s command in order to offer daily worship, not simply to adorn an old and rather pretty building with magnificent mood music for passing tourists, including aural tourists of the aesthetically beautiful. Some of the members of the choir receive communion during the services in which they sing, and have an insight into this mode of co-creation that takes on further meaning because it is a lively exchange between them personally and The Person. This is equivalent to the example of the boiling kettle. We can explain a boiling kettle of water in terms of conduction and convection, the boiling point and the latent heat of vaporisation of water, or we can look further to observe that the kettle is boiling because we would like another pot of tea. White, no sugar for me. Thank You! How do you take yours?

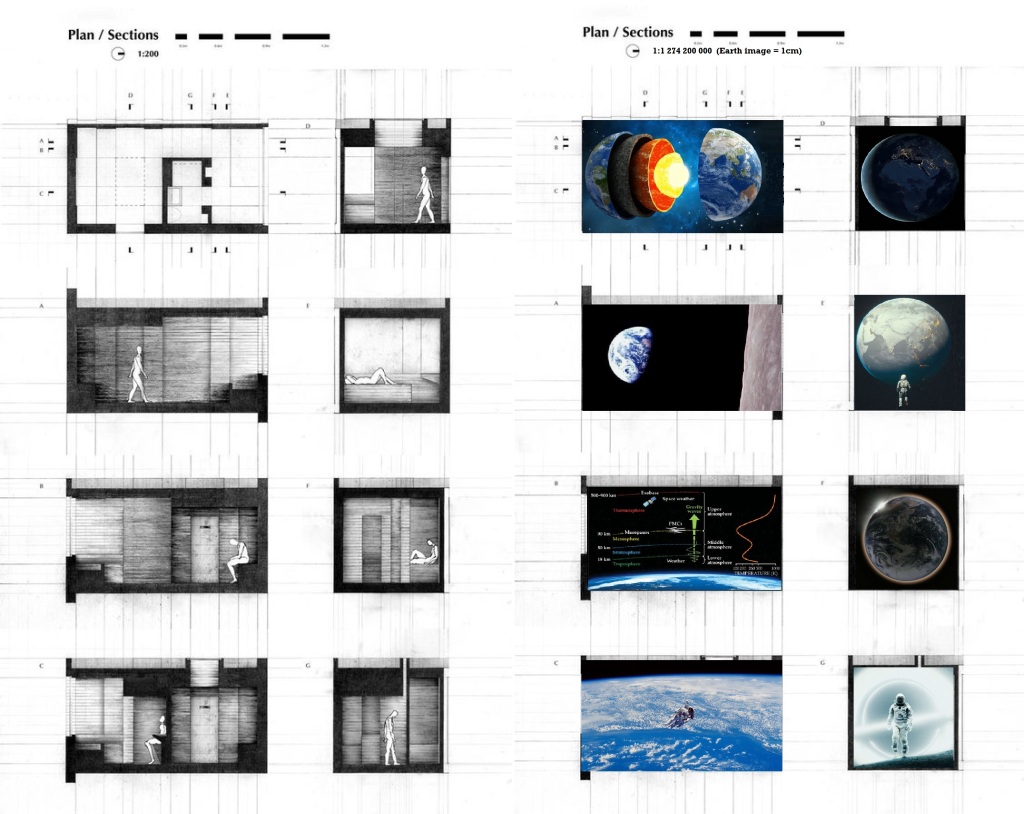

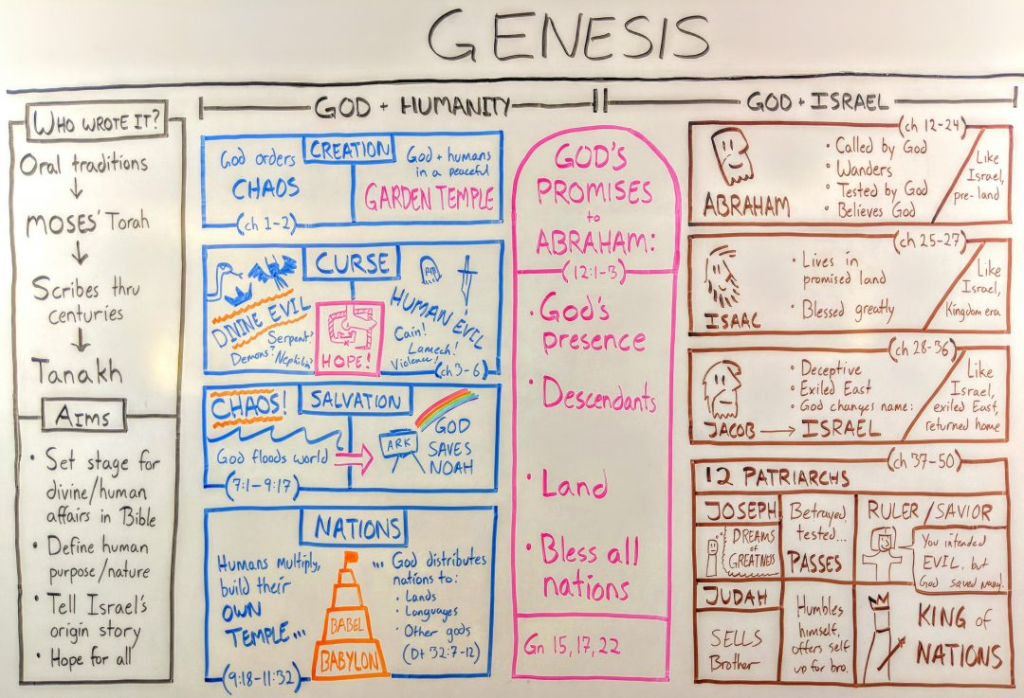

What follows is both Executive Summary (succinct statements in a technical style) and also some technical justification which did not appear in the original posts. Ironically therefore the first example is longer than the original post! That can be what happens when you are absorbed by scripture, but this also directs us to a principle. Genesis has 1533 verses and 20613 words (depending on which Hebrew version you consult) which occupies less than 90 minutes of a recorded reading. (That becomes some 32000 words in English, so you’ll have to read a bit quicker.) This blog is ten times as long as Genesis right now. I have shelves of books about Genesis, while the university libraries have slightly more. So Genesis is an ‘executive summary’ that skims over most or all technical details but flags up what is significant for the audience that needs to use and apply what could be looked into in much greater detail. It is for those that will execute action in life: the co-creators! This is especially the case in the opening chapters, as they deal with the aspects of the beginning that we could not grasp because we are human creatures. Each part is a ‘black box’ mechanism that has inner workings that are a mystery simply because they are hidden, yet the device has a specific purpose that can and must be properly appreciated. This blog aims to understand what those purposes are, and how they all fit together. I am saying that Genesis itself adopts an heuristic attitude, enabling discovery learning by all its readers, across generations and cultures, in a pragmatic and practical manner that is inclusive, insightful for the masses and open to useful application. Nevertheless, as it is couched in language that is more like the parables than laboratory reports or historical accounts, we are likely to need guides and interpreters to point out what is and what is not significant; what are proper and improper means of use. A further definition of heuristic is by trial and error: I have certainly been down some erroneous paths, barely surviving to make the return trip.

The first post is a reflection on the six-plus-one-makes-seven-days structure of Genesis chapter one. Right at the start of the blog I make a statement by implication, but the reader is left to work this out for themselves. I’ll spell it out for you now: Is it important to focus on the ‘creation week‘ as a claim about what God actually did in the beginning? Answer: No. Is Genesis giving us an insightful account into what God did (in terms of creating this cosmos, in a technical sense) and in what order in the opening chapter? Answer: No. Is it important to think of the Hebrew word for ‘day’ (yom) with regard to the two previous questions (i.e. 24h days?). Answer: No again. So why didn’t I spell out these things at the time, though I am doing so now? Answer: They are indeed important questions, but only in as much as they are to do with the overarching question of how we should read Genesis chapter one (and following). How do we really hear what the significant messages and claims of these opening words of the Torah are? I directed our focus to a different set of ideas about creation in order to address this constructive question. Is Genesis telling us about making out of nothing, about making continuously/ continually, or about (re)making out of what is there already? Or combinations of the three? Answers: Yes and Yes. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, in his dense little book, Creation, delicately makes the assertion that we (especially those of us who exercise our curiosity scientifically) cannot possibly know what happened at the beginning, or what God did at that time. How could we possibly understand? he says. We find ourselves in the middle of things as God has brought them to be, and continues to sustain them in their being. Bonhoeffer might have pointed out that we barely understand what the cosmos is like and certainly do not understand how it continues to be; that being so, the very idea of gaining understanding about the beginning is simply ridiculous. But we are wracked and wrecked with hubris, so we imagine that we might soon make sense of what truly lies beyond us. So abandoning all that perhaps leaves us ready and receptive to asking better questions, such as, ‘What is Genesis really telling us?’ My post makes this suggestion. God is addressing us directly, in the guise of a account about what God did at the beginning, to teach us about various facets of what Creation is about, and how we can be partners in it with God. The day and week framework is a direction to application by us. In its very form Genesis 1 is saying, ‘Here is how God sets you a pattern for creativity in life; watch, learn and imitate!’ Some things are made from nothing: creation ex nihilo. Others are made again from what went before, such as in modifying what we found and made in the world yesterday; creation ex vetere. And some things go on developing, being continually in formation, because what was made yesterday was good then but can go on maturing: creation in continuo. This conceptuality includes, though is not limited to, evolution in our modern scientific senses. For some Christian folk who I do hope will be reading this, ‘evolution’ is a word that has acquired a bad reputation, which is often why I have tended to avoid it in the blog so far. In as much as Science has been able to establish any mechanisms at all, I believe that ‘evolution’ is a reasonable shorthand for the means by which God has brought about this cosmos and whatever life is present in it. (If you are now chocking on your coffee, please re-read the first clause of that last sentence.) This is the approach I bring to what I teach in UK state schools. {That link takes you to my whole website for teachers.} However, there is much philosophical freighting of the term evolution, and that ‘reasonable shorthand’ should not be read as extending to such issues.

In the past I have sometimes been accused of giving an exposition or reflecting on scripture but not giving sufficient attention to application. Well, I am now saying that Genesis 1 is mostly about application. It is not so much giving a description of what God did, or how things went on to (re)make themselves- those are the proper tasks of science, or at least the second one is- but rather a more personalised lesson for the original hearers and us, in the here and now. What does it mean to be in relationship with the God of Creation, whose activities are ultimately mysterious to us, however advanced our science might become? If we are God’s children, made in God’s image and likeness, then we should first of all come to understand in a profound and meaningful fashion what God is like and how God works (in the sense that an attentive young child comes to feel at home with their father and mother and their habits, although they have no idea about most of what the adults do each day) and thus how we might form our own vision and habits after that pattern. Importantly, having sufficient understanding of the word and will and way of God to be able to judge rightly that we are, by the sufficient grace of God, walking accurately in step with Godself. This childlike understanding and aim is evoked by the photo accompanying the text, where children are following one another by example, and stepping into the hopscotch boxes (equivalent to each day of our living week) one after another, in necessary sequence. Our co-creating with God is therefore necessarily bounded within our lives in time, in days and weeks and all the seasons of life. And Genesis shows us, in the metaphor and pattern of chapter One, that God has stepped ahead of us to set a pattern in which we can see His Divine Example, and then imitate and even partner, very much as junior and lesser partners, with God, as God decrees.

To return to the metaphor of the view from the dangerous cliff edge, you will see that we are invited to join God on a good journey in life. Part of that journey involves wondering how it starts, and in Genesis we are directed by the certified Guide. We want to visit the most spectacular vistas, but that is fraught with risk. Both the Guide and the safety signage provide the cautions we must respect in order to travel safely and enjoy the panoramic viewpoints. It would be great if we were always humble enough to travel with a wise Guide and not question their instructions, but that is not the human condition. The most impressive viewpoints demand that the warning signage is planted right where the view is, and that is likely to spoil the picture. That is why I did not spell out the negatives in blogpost 1. I aimed to affirm what Genesis 1 is saying, without spoiling the moment by sticking up unwelcoming signs. It really puts people off.

This is exactly my concern. When I was a young Christian I was greatly discouraged by would-be guides who were very quick to tell me what Genesis didn’t mean, and pointed to science for better answers about origins. Tragically, although they were Christian people, they couldn’t really tell me what Genesis did mean. Their proper desire to be a clear warning signpost wasn’t effective, and I feel that the cliff collapsed under us all. Or to switch metaphors: in wars, some poor folk get shot by their own side. This blog is written in hope that we might avert friendly fire incidents.

Once again, to adopt an optimistic stance: in this first post I am signalling one of the vital elements of creation theology that was completely missing from the Young Earth creation approach. In the view of Ken Ham and those of his persuasion, the reason for searching out ‘Answers in Genesis’ is because the trajectory of God’s Kingdom plan takes us ‘Back to Genesis’. The gospel story, says Ham, leads us through God’s salvation plan in Christ to undo the wrongs done in Eden and to return us to that blissful state as God’s redeemed people. This is the somewhat like the error of the ancients, to assert that history is a repeating cycle. But Henry Morris, Duane Gish, Monty White and my other teachers were making an incorrect assumption in asserting that Genesis ought and should be read to exclude the operation of evolution as a partial mechanism of God’s creative actions, past and present. They were right to operate on the assumption that God’s Word should hold sway over and above the limited insights of humans, some of whom plainly set out to harness rationality for atheistic ends. But the cosmos God created did then evolve, once it was formed. This being so, we need to return to the biblical texts, including Genesis, to better discern, with God’s aid, to learning the lessons the Bible really offers to us about creation. Crucially, we are in the middle, as Bonhoeffer put it, between the first creation and the second creation, the ‘New Creation‘ of the last book of the New Testament. Creation must be properly understood as the activity of God both at the start of what we now see as life and also at its temporary conclusion. Our American Christian young earth creationist friends jocularly described ‘evilution’ [their misspelling inspired by certain accents, to assert the wickedness of this allegedly antibiblical concept] as the idea that we originated ‘From Goo to You by way of the Zoo,’ and therefore that authentic Christian confession should be grounded on the belief that Genesis gives a scientifically literal account of what happened, and so there need be no argument about whether Genesis is scientifically or theologically revelatory. The first is so, and the second follows straightforwardly. I was happy at one time to work according to the hypothesis that God could have made the cosmos in this manner, but I no longer have any need of that hypothesis. We err if we accuse God of either inability or incompetence. It now is plain to me that we engage in a category error if we expect the beginning of the Bible to be about science, but not what follows. The whole Bible (not just its ten opening chapters) is a testimony to God’s Creation project. It starts with a theologically-framed introduction to creation (including ‘nature’, as we frequently describe it- terminology perhaps embraced as it unhinges creation from Creator), takes us through the journey of salvation history with Israel, Christ the Messiah and the Church Age, and alerts us to the theologically-framed announcement of the second, New Creation, in which life (as biblically understood and formulated) will be seen to transcend physical death and transition through God’s making all things New into all-and-whatever marvels and mysteries lie ahead in our being as the Body of Christ. ‘From Goo to Glory,’ if you will. It is a reductionist error to assert that the Genesis scriptures are ‘about’ the processes of scientific origins. What we should have said is that coincidences between the humanly accommodated narratives of the Hebrew bible and the findings of cosmology and palaeontology are not significant in what the message and meaning of the revealed scriptures actually is. What we should be saying is that the fact that we are created in the image and likeness of God and that we are fleshly creatures made (we now understand) from recycled stardust and evolved genes is the basis of the Incarnation which we celebrate at Christmas. What we should be saying is that in the Will, ability and competence of God this present chapter of Creation will pass on into the next, though as with the first origin, we also understand next to nothing about how that will happen. What we should be saying is that it is no insult to the omnipotence of God to discover that the processes of atomic evolution took so long, or likewise the diversification of life through multiple iterations of the tree of life, most of which went extinct long before Homo sapiens appeared. (Or as Ken Ham pejoratively puts it, ‘evolution through death and billions of years.’) What we should be saying is that mortality will put on immortality, which is a claim that transcends science.

50 I tell you this, brothers: flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God, nor does the perishable inherit the imperishable. 51 Behold! I tell you a mystery. We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, 52 in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we shall be changed. 53 For this perishable body must put on the imperishable, and this mortal body must put on immortality. 54 When the perishable puts on the imperishable, and the mortal puts on immortality, then shall come to pass the saying that is written:

“Death is swallowed up in victory.”

1 Corinthians 15:50-54 ESV

Note that ‘transcends’ does not mean ‘contradicts.’ As I explain in the teachers’ website, some of the things that happen can be described and investigated scientifically, but others cannot. This is only to show that Science is a limited discipline that, while generating much knowledge and thus the potential for us to manipulate the world for good and ill, puts no limits at all on what else God can make possible. Call that miracle if you like, but don’t suggest that God is somehow misbehaving when such ‘irregularities’ and the ‘unusual’ occur. Ken Ham and Co are right to join Karl Barth in emphasising the vital necessity for revelation. We can trust the significance of the resurrection of Jesus Christ at Easter, on Sunday the 5th of April 33AD, because God has given corroborated testimony to all of humankind in the four New Testament Gospels, and in the consequential effects in our shared history that followed, beginning with the Book of Acts.

In sum, my first post at least hints at these assertions about the doctrines of creation in Genesis 1. God is the pre-existent One, the Creator of everything. Everything, including us, depends on God. God freely chooses what to do, and gifts us with freedom to do likewise. In the creation week we are beckoned into a partnership relationship with the sovereign God of all, a partnership that has physical and spiritual hands, best exercised in tandem, where our ‘business’ and our ‘prayer’ are equally active. Through this partnership we can transcend the natural creativity of the humanists to co-create with God in remaking what was already there- perhaps including the repair of what was broken. And in developing what was good yesterday, and progressing to what is even better. And even in creating from nothing, making things that were not, from our sanctified imagination, especially at a corporate level. The positive claim is this: there are creative creatures in God’s world, including Cactus finches, Japanese macaques and sign-language speaking Gorillas, as well as moonwalking Men. But it is God’s imago Dei human beings that have been invited into a divine covenant that can respond to God’s gift and call to partnership, to co-creation both in the here-and-now and also in the hereafter. We can discover the fruitfulness of this relationship one day at a time.

Introducing myself as a ‘Common or Garden’ Theologian

This blog is being written as an alternative to something else. It was conceived in the spring of 2020, as the lockdown period of the COVID-19 pandemic extended across the UK and beyond. My progress as a serious student of the intersections of science and the Christian life had passed well into its third decade, but I had yet to commit myself to print to any significant extent. A long period of postgraduate study under the supervision of a significant thinker in science and theology had enabled considerable progression in my development, and opened the way to many significant opportunities, but I did not find the format of the academic thesis to provide the appropriate setting for what I really wanted to say. I may return there another time, for there is great value in the intellectual rigour of that format. But the unexpected and unpredicted opportunity of extended lockdown enabled this blog to form in the moment that was March 2020. Tempus fugit, carpe diem. and all that. But crucially I decided I was ready to use the sandbox of a blog to attempt the more or less instant formulation and publication of my thinking that had had been shared in a limited manner at that stage. Not so much that time was passing, but rather that The Day had arrived.

I considered what the blog could be called, and how I would formulate this space in which my musings would take form and flight. My personal life motto is ‘Word into Life’, which straddles books and living experience, teaching and learning- which are what I’m always doing, one way and another- and it also encapsulates my specialisms. Genetic code becomes living organism, and the Word of God is offered to individuals and the world as the basis for Life- the life of men, and the basis for Life in the Eternity of God. How exactly to translate that into a lively and appealing title heading that would forge an organic link between the personal and the profound? It came to me more or less in an instant.

“Common or Garden… theologian.”

A thorough search ascertained the important criterion of originality as a blog and web identity. More excitingly I discovered very little evidence of the use of the concept anywhere, and what I did find was deeply encouraging. First, I found a quote, still unsourced, attributed to none other than Karl Barth, who described himself thus. Sometime I will get to a specialist library to get to the bottom of that original occurrence- as far as I know. The only other use was by Gerard Mannion, Irish Catholic theologian who passed before his time, aged just 49 a few months before the pandemic started. Until I looked up the phrase, I’d never heard of Mannion. He deployed the phrase in a letter defending another academic who was under the sort of persecution that Galileo would have related to. I haven’t written my extended reflection on these resonant coincidences yet, but I promise to do so. Suffice to say I had discovered a label for the space I intended to fill with words that was just the right shape: a round hole, waiting for a round peg.

And as the Sproul quotation about all Christians being theologians conveys, the conceptuality of ‘common or garden’ was exactly what I was looking for.

[I find that Barth said the same thing. “In the Church of Jesus Christ there can and should be no non-theologians.” And that’s not all. Maybe some Christian folk understand how important it is that theology shouldn’t be limited to theologians. “Theology is not a private subject for theologians only. Nor is it a private subject for professors. Fortunately, there have always been pastors who have understood more about theology than most professors. Nor is theology a private subject of study for pastors. Fortunately, there have repeatedly been congregation members, and often whole congregations, who have pursued theology energetically while their pastors were theological infants or barbarians. Theology is a matter for the Church.” – Karl Barth.]

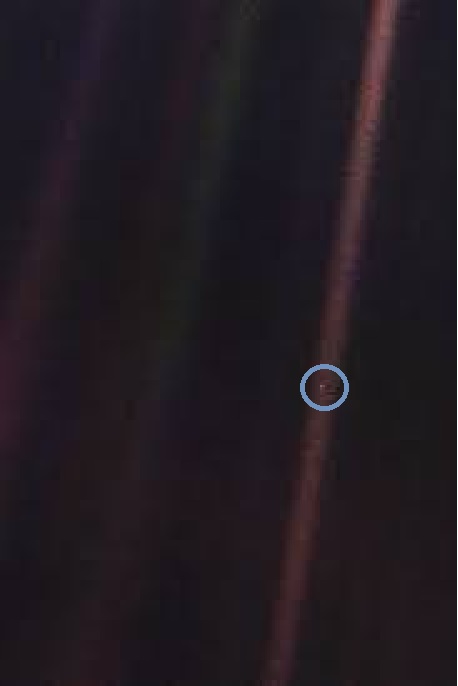

Everyone is included, potentially, if we will- and the will of God is that we should agree. There is room in the plan and grace of God for everyone’s thriving. ‘The boundary lines have fallen for us all in pleasant places,’ as the psalmist put it. The proper theology of Creation is not to be limited to arcane and abstract exercises in academic boundary work between the Jewish-Hebrew worldview and metaphysical musings on the philosophy of stellar and biological evolution. It certainly includes that- but what I had settled on as my core message, that God wants us to create the future with Him has much wider compass- which should be no surprise once we realise that the vast and ancient cosmos of which we are part is required in order to enable the existence of this pale Blue Dot, Earth, that we currently know as our Home. ‘Creation’ is not a doctrine of theology or of science that is chiefly about the past. Rather, it is about the Present, our shared gift of the God of Creation who makes and sustains us all, which is continuous with the Past- because God is consistent and reliable- and reaching into God’s Future, which God invites us to continue to share. The doctrine of Creation, I now see, is as much to do with the experience of conversion that believers share as the more familiar aspects of ‘the gospel’. And it should underpin our shared life as the people of God in God’s world, in which we find our opportunities for individual growth and expression. As I meet the Lord Jesus Christ, I find myself, coming to know Him and me and you all at once, though we are on our own various journeys in life.

At the time of writing my introduction, those ideas were expressed in my brief reflection on the bible character of Stephen in the book of Acts. I won’t rehash that here. Suffice to say that my retelling also reflects on the Genesis phenomenon of Naming. We observe as a truism that we generally come to judgements about (people/ even things) on powerful first impressions, and one of those impressions is the name. Names are given, and the creative act in question is the choice that our parents make. As God brought the animals to Adam, it says, the creative acts of God were augmented and in some way completed by the naming process. Of course, everything has to be called something, and it may typically seem that words are just sounds that signify distinction by difference in sound, but some sounds convey and confer more meaning and thus significance. I shared my personal understanding of my name-identity in the blog post, and then when my mother read it, we had another conversation that had not happened before. So we created some more strands in our relationship.

The big claim I made is that it is the proper business of the Christian theologian to situate themselves on the boundaries between the Words and traditions- new and old- of our living Faith and all the other aspects of human life in the gift and grace of God. For me, of course, this is what I see as a major expression of my own being a co-creator with God. This statement continues to astonish me, and I think clearly accounts for my reluctance to commit to other forms of formal work in the past. Let me be clear. The very concept of co-creation would be hubris, were it not the genuine calling of Christ to us all.

Unlocking potential: Joseph and lockdown

When teaching lessons in Critical Thinking to school students, an early class is on the topic of arguments. “Critical thinking means being able to make good arguments. Arguments are claims backed by reasons that are supported by evidence.” Here, my principal argument is that while it is true that Genesis is the preamble to the Torah account of the founding of Israel as the People of God and the means by which God brings Salvation to all, it is a mistake to underplay the significance of the doctrine of Creation in Genesis, as though what is being created is the people of God in the descendants of the 12 sons of Jacob who are a blank page on which the spiritual action of scripture is then worked out, ultimately in the Messiah. Why such a mistake? No one denies that the human beings who feature in the scriptural accounts have agency of their own, but the scale of this agency is, I am underlining, underestimated. Apparently, godly people really shouldn’t try to do very much. The evangelical Christian position is that at the Fall whatever free agency humans might have been able to exercise was fatally compromised, and the rest of salvation history is the work of God, in which the human contribution, very necessary and crucial, certainly, is best characterised by humility, obedience, and, most of all, the invisible function of faith. Since the basis of our rescued relationship with God is founded on death to self and faith in God, it is most visibly expressed in religious practice; worship, prayer and the quiet community activities of Church. The ‘working out’ of salvation as St Paul puts it is in the realms of private piety- or at most, in the exercise of the multifaceted ministries of helps, in public service, or perhaps somewhat reluctantly in the public facing calls and protest for social justice. What should the Christian attitude to business be? We aren’t quite sure, as the book of James seems to be somewhat suspicious of that activity. Does our present era of scientifically empowered technologies and the hankering for Progress have a basis in Christian discipleship? Is the Church of Jesus Christ supposed to have a vision for making the world better, or is that a heresy? The gospel is the means of escape from this world, and we are only sent, told to GO! back into the world, that wicked place, in order to preach and witness and snatch souls from the soon-to-arrive flames of destruction that will consume the world, the flesh and the devil. In the meantime, we should just support the maintenance of the status quo, in as much as it is peaceable and sustainable.

To continue with my reasoning: I think that while there is soundness in the general disposition of Christian mindset to value the eternal things, first and last, what the lives of the peoples of God will amount to in the hereafter after our deaths and the general resurrection and judgement- so of course the gospel witness to Jesus Christ is of paramount importance- this viewpoint overlooks God’s intention for His Creation in the here and now. The Genesis account, and the wider scriptural materials that provide us with a doctrine of Creation, does not tell us to give up on the world, as if it is a wicked thing and a bad place; that is the error of Plato. Nor does the Genesis account give us reason to abandon human agency and energetic human activity as expressions of the original creative intent of the God of us all, whether we own Him or not. The evangelist is right- we are fools to attempt to work for our salvation, as though we could earn anything that will count before the judgement seat of God. This is foolishness because all we need to restore our broken relationship with God is believing faith and reliance on the person and work on the cross of Jesus Christ. Salvation in no other Name! But the Church has allowed the theft of a crucial part of our calling as God’s human creatures: that we can continue as creative partner with God in tending and developing this good Earth that God had trusted to us all, and over which negative spiritual forces and personalities only have partial sway. This world, and our lives in it, may I say, whether or not we are believers in Christ, is still the proper place for working out our creativity in the common grace of God. I hope you see where I am going: And how much more so if we are believers in Christ and sharers in the conviction that life for everyone and everything can be so much better if we work out our eternal values in partnership with Immanuel, God with us, empowered by His Spirit.

That is my claim, and those are my reasons. What is the evidence to back up this claim and this reasoning? The book of Genesis, that is, all of it.

I love these poster summary diagrams, and I expect you will appreciate the animated versions at the Bible Project too. Jeffrey’s telling above is thoroughly sound and representative of the best. But this blog offers a specific correction or modification to this sort of telling. The traditional theological view has been that the first portion of Genesis is Primaeval History, and this is an important but brief prelude to the real action, which is God’s call to Abram and his descendants that bursts out with theological fireworks in chapter 12. This is the real start of ‘Bible History’, but even the life of Abra(ha)m is a muted testimony to God’s salvation-of-the-world project. The rest of Genesis still doesn’t deliver a spectacular new start- we have to wait for the Exodus for that: Moses and the ‘Let My People Go!’ stuff. The generations of Abraham’s descendants keep mucking up, though God doesn’t give up on them.

But hang on- do you see the last brown box bottom right in Jeffrey’s poster? That’s the life of Joseph, and his family- which covers chapters 37-50 of Genesis! That’s a lot of chapters and text simply to explain that Jacob had 12 sons that are the seeds of the people of Israel (Jacob’s other name) who will later be rescued by the power of God and God’s spiritual leader Moses. And there is a lot of emphasis on the agency of Joseph in these chapters, an agency that is blessed by God, but where we see Joseph’s agency in the foreground, and God’s blessing in the background. And at what a scale!

In short, my evidence is in an appeal to the whole book of Genesis as the basis for our proper place as co-creators with God in the now, a status and scale of calling that can still have world shaping consequences. A scale of potential impact that is significant even in a pluralist society, where those who see themselves as God’s people can work constructively with others who own a different god or no god at all, to the benefit of all. What God started in God’s charge to Adam in the Garden is still in effect; it has not lapsed! God wanted Adam and Eve to co-create in His Garden, and we see this capacity continue after the expulsion from Eden. Supremely in Joseph, we see this potential realised: what God intended for Adam, but was not realised due to the turn to sin, is yet realised in Joseph. Genesis comes to a spectacular conclusion in two ways- one familiar, the other less perceived. God doesn’t give up on humanity, or, indeed, his whole creation project (as Noah discovers), and so Israel finds its genesis as a nation in Egypt (Genesis to Exodus). But in addition- this is so important- there is also a significant deposit of revelation in the Joseph account that God does not want us to step back from the proper exercise of human agency in this good world, even once we have grasped the ghastly implications of our spiritual predicament before the Eternal Judge of All. God’s work to bring salvation in the world God ultimately owns is mysteriously subtle, hinging on the smallest but crucial human responses (eg Abraham and Isaac in Gen 22). The co-creative work of God’s faith-living people is also subtle in the main, and especially so in Joseph’s case- we are schooled through his slow elevation until he gains willing hearing in the foreign culture that is the ancient Egypt of his common slavery. He becomes second in the land, charged by Pharaoh to till and watch over his whole country in advance of a tragedy that he has only dreamt about. There is no change to the mortal end of anyone, but in Joseph’s co-creating leadership we see the full potential for a life of piety and good character worked out even to the saving of nations in the greatest global disasters. Above all, we see that God’s intention is to nurture hope in His human creatures, a signpost to life hereafter.

The Genesis summary diagrams need to be redrawn. My story here is a contribution to that project, written in the context of the new COVID pandemic, when we could only dream of the scale of disaster, or of the possible means of rescue. This is its first chapter.

Like so-called ‘Easter eggs’ in popular movies, I allude to several Genesis themes and tropes in these pieces on Joseph, in order to emphasise continuity and connections between the parts of the Genesis narrative.

Joseph’s dreams reprise the creation of heavenly bodies, and recalibrate our understanding of what Genesis is ‘about’.

Just as God accompanied Cain, so He accompanies Joseph into exile: Immanuel in embryo.

Following Joseph’s betrayal and enslavement, (cf chaos over the waters) Joseph is blessed by God, and his life progresses from good to very good (cf God’s pronouncements in Gen 1).

Following the principle of naming in Gen 2, Joseph is known as Hebrew (man of God) while his accuser is Potiphar’s Wife. The imago Dei is worked out in their identification and description, even though Joseph’s mistress makes choices at odds with divine intent.

The reality of experience as a prisoner can also be read to affirm human agency at all levels. There is no fantasy here. There is divine intervention, but the balance of emphasis is on the interplay between human character and rational consequences.

As he matures through human trials and circumstances, Joseph is at work in God’s good world, broken though it is at all levels of human society. There is a continuum in his work, between what we might have called ‘secular’ concerns and ‘spiritual’ ones. There is, in fact, no distinction in the Genesis worldview; no difference in value.

The furnace and cauldron of destiny is in the heart and mind of the man of God, in the integrity of his being, and of the liveliness of relationship with his God and neighbours of all sorts and levels of seniority.

I then make the leap to suggesting that imagination can be equally harnessed to the challenges of (false) imprisonment (illustrated by the case of Terry Waite) and also to technological challenges, including unlikely cases of lighter-than-air transport. I am making the point that the lessons of Joseph’s thriving in oppression and imprisonment apply in our current circumstances, whether that be a life-threatening pandemic, or otherwise.

As I set out criteria and explore the potential of the co-creator concept, two points must be paramount. The first is that while we come to take more seriously the implications of being made in imago Dei, we remain the junior partner to our Sovereign Divine partner. “Co-” does not mean equal, in any sense or form. The second stems from the first; God is in supervision of the timing of the opportunities that arise for human agency. In this case, Joseph’s deliverance and elevation awaited the invitation of the True God to Pharaoh, and this was synchronised with the (distantly) impending (global) famine. And yet, to repeat, God does invite His people into partnership within these constraints, and the potential for radical co-working is still considerable. At the time of writing, this had a ready application in regard of prayer and adaptation to the developing COVID challenges at all levels of our lives.

Interpreting troubled times: Joseph and COVID

At the start of the Genesis 1 creation account, God’s considered work begins in the context of ‘chaos and void’, or tohu wa bohu as the Hebrew has it. This is notable as this narrative element is a key feature even of the initial chapter in which God is depicted to be in sovereign control, and each day’s good work is brought to a very good conclusion. Perhaps this makes it easier for us to consider our beginning in each new day, whether in circumstances of lockdown or trial of some sort. The circumstances in which Pharaoh is made aware of God’s man in his jail come about through his awakening from disturbing dreams and finding that his spirit is troubled. The first recorded work of God is described in troubled circumstances- and so is the raising up and releasing into influence of his imago Dei man Joseph in Egypt- from ignominy and incarceration to grand office and gilded chariot.

We will affirm, no doubt, that God is properly concerned about the state of the world, and the state of each nation within it- the big concerns of the world are indeed God’s concerns. Yet we don’t often see evidence that this concern is expressed, or that God’s people are motivated by concerns at the macro scale. We default to our local and individual concerns, even seeing this as the proper spiritual response. The big stuff is concealed and shrouded in mystery, marked only by naïve platitudes and sweeping generalisations. “God’s in control. It will be alright in the End. God’s plan will prevail.” And suchlike.

It’s not really our business.

‘Lord, my heart is not haughty, nor my eyes lofty; neither do I exercise myself in matters too great or in things too wonderful for me.’ Ps 131:1 AMP.

That is not the picture painted in Genesis 41. Seven years ahead of global disaster, God disturbs the waters of the heart of a heathen ruler. God has his imago Dei partner ready in the wings, and the stage is being set for the announcement of God’s ambassador to the greatest court on Earth at that time in history. And this ambassador is not simply the representative and mouthpiece of the Almighty who speaks to the near and eternal destiny of all peoples- Joseph is also offered as God’s co-agent, and such he becomes, for he is filled with God’s Spirit.

God’s prepared boy-become-man Joseph, tested, human, frail, and faithful, blessed and prospered by God ‘who works in mysterious ways His wonders to perform’ is the person in whom attentive listening and observation, analysis and interpretation, wisdom and revelation all come together, for these are the marks and qualities of God’s co-creative partner. Crucially, these are all inextricably interwoven with a fulsome appreciation of the world as we see it with all our human senses. Joseph is an educated man, in the sense that he grew up in the realities of farming and animal husbandry and the ways in which those activities underpin survival and culture. So as he humbly speaks in Pharoah’s courts of God’s intention to sustain Egypt’s survival into the distant future, this leads to practical assertions of strategy. He does not settle for a nebulous invocation of blessing (compared, say, with a popular decontextualised quotation from Jeremiah 31) but follows on from the inspired and accurate interpretation of Pharaoh’s double dream to the action points and detailed content of a Governmental Policy that should be enacted at scale- the whole community, for and involving the whole nation.

In the purposes of God for raising up Israel as His people, this lesson was not remembered, but it is recorded in Genesis for such a time as this. The principles and purposes of God in partnership with God’s people have not been changed or lost. Though we may need to be reminded.

The example and lessons of Joseph in Pharaoh’s court must surely include that God does intend our revelatory reasoning to win the day in courts and offices of state. However rarely, imprecisely, temporarily or otherwise qualified; nevertheless, the yeast can have its effect throughout the whole batch of dough and work effectively to its complete transformation into a healthy and sustaining thing. The small dose of salt will be tasted- a transformation in flavour and satisfaction, and a profound preservation of the whole, extending life. In both metaphors we see a prophecy of transcendence of this reality that begins in this reality: life blessed in the now that leads to blessed life hereafter. Under God’s blessing, our fragile and evanescent lives can be set on a path to a Reality that is less tenuous, death is pushed back with hope, and where Promise is realised.

Crucially, I put a case that the proper concern of God’s leaders should include skilful knowledge gleaned from science, medicine and technology. The COVID pandemic is an exemplar of this, where learning from Scripture and all our Scientia synergises to “a wisdom that can bring together the pertinent considerations of medicine, statistics, science and society, spirituality and piety, business and farming…”

We note the ways in which the clamour for action especially when we are confronted by disaster- ‘something must be done’- inevitably leads to a cacophony of voices in the public square where the worst motives and weaknesses in character of leaders and would-be influencers at all levels are exposed. It is in this regard that the good character of God’s people can also provide a crucial resource. It may be the crucial resource. Others may be more knowledgeable and more skilful- but that does not mean that ‘the science will be followed’ or that best efforts will be deployed. And this is yet a hard lesson for God’s people, who have not always given proper attention to the growth of rounded and wholesome character that is called for in this regard.

I refute the traditional model of piety that sees its fulfilment within the context of church meetings. This ungodly motive led to the unreasonable call to open church buildings and allow considerable numbers to meet for ‘vital’ worship, thus leading to new waves of COVID infection and the untimely death of congregants and leaders alike. From my later perspective looking back on this blogpost, I am happy to allow that there may have been appropriate expertise in Sweden’s privileged case (see footnote), but that it is plain that the uncontrolled spread of coronavirus in Malawi and much of Europe and America was tragic and only controlled, if it was controlled at all, by energetic restrictions on community mixing and contact. The human cost has been considerable; I mention Malawi as a local Christian minister there at the time told me of a swathe of deaths of Christian leaders that has now left the country further bereft of vital leadership. Many died because of their denial of the realities of epidemiology. The God of miracles is the same God who inspired Leviticus 13 to 15.

So we need to strive for a much greater maturity in our considerations of faith AND science. The quality of leadership I am calling for must be more properly informed and considered in this respect if we are to be of real service in the world in this present century, and if there is to be a positive legacy from the community of faith as we face challenges on unprecedented scales in the near future.

Footnote. For clarity on the question of proportionate lockdowns, I include this quotation from the Daily Telegraph on 23 3 23:

In March 2020, as, one by one, every country in the Western world succumbed to panic and imposed a lockdown on its population, Sweden’s state epidemiologist held his nerve and stuck to the plan. The Swedish people would be given sensible advice and told to work from home wherever possible, but apart from a ban on gatherings of over 50 people and a few rules for restaurants, any Covid measures were entirely voluntary. Anders Tegnell simply didn’t think the evidence supported a lockdown. A veteran of the swine flu pandemic who had worked with the deadly Ebola virus, the 63-year-old doctor wasn’t going to do something unproven or plain stupid because a lot of over-heated people were yelling at him to do it.

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2023/03/23/anders-tegnell-swedens-pandemic-plan-lockdown-never-agenda/

Obadiah, God’s secret leader in crisis.

I claim that Joseph is presented to us in Genesis 37-50 as the epitome of becoming a human co-creator with God. [Very much in the context of the lives and decisions of his wider family, both parents and siblings.] And that the concept of co-creator is not the exception, but is to be a pattern for many. So there are other biblical examples to draw out and reflect on.

One of the five biblical Obadiah’s features in 1 Kings 18; he may have started out as a regular guy, but he becomes exceptional. By contrast with Joseph, Obadiah is a bit-part player in the royal court who is not further promoted. Many of us work for someone else, taking care of their agenda, our work bounded by our duty to their vision, not our own. In this creative exploration- a story as much as it is a study- I wonder what it might mean to be a co-creator in terms of being (to use modern categories) an employee, rather than as the CEO (or second in the land, as Joseph became).

Very deliberately, my version of the story is couched in the language of business, and in terms of economic realities as we currently typically understand them. This sets the foundation for what co-creation might look like in what is everyday life at work, in the social marketplace, for most of us most of the time, and even more so in circumstances of change and growingly acute crises. 1 Kings 18 shows us an example of what it means to ’till and watch’ in our responsibilities in the world, and especially in as much as we have to work with the (obviously) ungodly.

Obadiah is held up to us as an example of a man who is trusted even by the oppressive and godless King that is Ahab and his ghastly wife Queen Jezebel. It is this depth of character and commitment to the ethics of service that Paul evokes in his letter to the young leader Timothy: 2 Tim 215 “Do your best to present yourself to God as one approved,[b] a worker who has no need to be ashamed, rightly handling the word of truth. ” Note [b] says, ‘That is, one approved after being tested.’ Which is certainly what we see in 1 Kings 18. [And compare with the Eden garden incident, and then with Joseph in Egypt.] What is more, Obadiah’s service is given in the context of deep ethical compromise and the most challenging and uncomfortable circumstances. But all these drawbacks do not disqualify him from the status of co-creator/ co-worker in God’s economy. He lives under an open heaven- God sees him and knows his motives, opening opportunity to preserve kingdom values in the midst of aggressive chaos. The man of God is no doubt himself in danger, considered from a human perspective, and yet he could not be safer, as the scripture maintains.

This reflection emphasises the anti-romance of being a co-creator, a walking-by-faith co-worker with God. The approach of fear is palpable, for the causes are, all too often, multiple and immediate. The partnership that develops between the two men of God in this account also emphasises another important truth: though we are a family/ team/ church /alternative collective and dynamic relationship structure, our roles and gifts are absolutely not the same. The parts we each might come to play as co-creators with God will not be equal, though that is also a factor over which we have some influence. In the final analysis, your role and mine will not be of the same mode, order or opportunity. Obadiah has his roles, while Elijah has his. God alone is sovereign, while each of us finds our own constraints and freedoms.

Most counter-intuitively of all, Obadiah’s experience in this account is that God is not limited to creatively partnering with us in the times of shalom peace- in the spring sunshine of ethical and moral comforts. Not at all; the co-working of Obadiah alongside his spiritual senior Elijah, under the all-seeing gaze of our Great God is brought to its climax in the prophetic confrontation of righteousness and wickedness- this sets the scene for the miraculous breaking of the drought and all the consequences thereof. To repeat: co-working includes confrontation, a creative act that is absolutely not trivial. What is particularly instructive is that God brings Obadiah into the circle of influencers in God’s world: Obadiah becomes a co-prophet, alongside Elijah- an equality in significance in God’s Kingdom coming work, even though not equality of role. And God sees his faithful service, and then tells all his story in due time.

Creating community with concrete

In the last post I explored a biblical narrative of the life of one of God’s co-creators in the form of a story, transposed into our present. This itself is an aspect of what co-creation is about: the melding and interplay of all modes of creativity, as particular expressions of form enhance the expression and communication of meaning. In this next case it is a sermon that is the delivery formula. I claim that the communication vehicle has agential effect, alongside the objectified and abstracted content. (The next post will drive this point home even more energetically.)

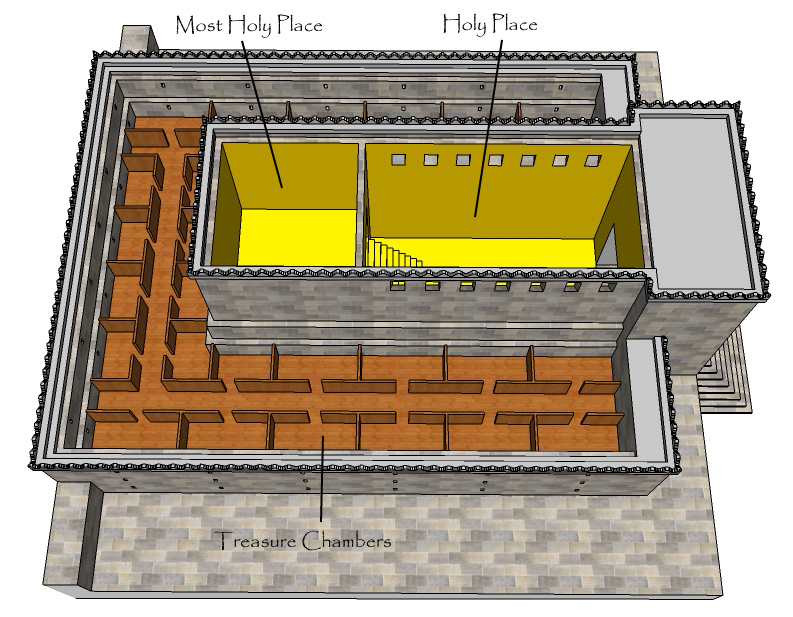

In this sermon for the occasion of the celebration and opening for a new church building in a remote Kenyan village, I set up a creative interplay between scriptural accounts of the meeting of God with God’s people at the Temple of Solomon, and then at Pentecost, with the current needs and vision of a local community in Kenya I have had the privilege of living life with over a series of visits. The common felt need was for a building in which the worshipping community can meet regularly, combining shelter from the elements (as when it rains, it really chucks it down!) and the benefits of security and time saving that comes with one’s own property. But more than this, the whole local community might benefit if such a resource is shared and used for the common good. The vision I am championing is that of the European medieval building where the Sabbath meeting place is used for further community benefit as market space and meeting house on the other days of the week. In rural Kenya, this is making the costly investment much more beneficial.

And there was a further dynamic in this development. Over the course of my visits and building friendship-partnership we were able to reflect on a number of practical steps for development that could be brought under the heading of spiritual progress. If community aids to control malaria are successful, the whole community benefits, and we need not argue if this is a spiritual or practical matter- to be blunt, these categories ought not to be pitched against one another. If cooking is done over three stone fires, fuelled with locally sourced timber, this affects all manner of aspects of society, not least the polluting of villagers huts and the general contamination of the air all must breathe. Is this a spiritual concern? Yes. Is this a concern that can be considered as amongst the proper activities of churches and church leadership? Absolutely. The community meet most weekends to hold a funeral for some neighbour or other, as the health impacts of the lives they live in such reduced circumstances are chronic and acute. Does God believe in progress? I suggest so: the blessing of God’s anointing filling fire at Pentecost is much more environmentally friendly that it was in Solomon’s day!

This sermon therefore takes one example- improving the techniques for cooking in health sustaining ways- of our growing awareness of the challenges of sustainability, environmental health and the climate crisis to bring this whole area of current concern within the ambit and aegis of church leadership and vision for development. My claim is that the sermon itself is a proper vehicle for both the message and the work, or ministry if you like, of the people of God: just as we watch and take care of the business of people and their souls, so also at the same time and in the same words we watch and take care of the sustainability of planet and all that stems from the good gifts of creation that God has placed under our sacred stewardship.

Which comes first: the wine or the wineskin?

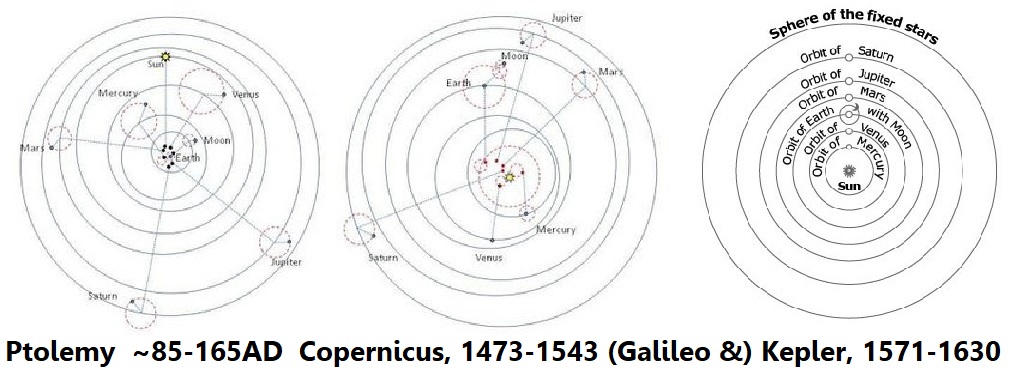

I start at the deep end: to what extent can we deal with the question of ultimate origins? In what ways does Genesis (chapter 1) give us assistance, or offer insight, into this profound enquiry? I offer some science-and-theology analysis in a brief non-technical manner.

I draw a parallel between the creation-of-Israel account in Exodus with the creation-of-everything account in Genesis, linked by the spoken-words-into-life dynamics of Moses in partnership with God in Exodus. In Genesis the Divine utterance that forms and shapes every thing has no assistant- unless we count the Spirit that hovers (or broods) over the waters. Is that too dangerously close to the theological anachronism that is New Testament theology of Trinity imposed on the monotheism of orthodox Judaism? Yes, and then again, perhaps not, as the figure of Wisdom accompanies the creating Divine elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible. Or perhaps the seed is being sown that we, the readers, might become the co-utterers of these creative words, even as we read them aloud to the congregated hearers. In this analysis we may approach the time and place where the Beginning was, but we certainly will not go through- that is impossible!

Most significantly is this claim: that the first Divine creation, ‘Let there be light!’ finds this parallel in the mouth of God’s foremost servant Moses, ‘Let My people go!’ The called and commissioned human creature becomes co-creator with Godself, uttering God’s own creating-by-speaking words. As Moses speaks and names My people, so that is what they become, though through labour pains and the resistance of the then-Pharaoh.

I continue in the same metaphysical vein: we partly understand the dynamics of words in our world, though they are still yet mysterious. I evoke this mystery by discussion in terms of the plasma of incendiary combustion that undoes the three-states-of-matter classification of solid, liquid and gas, and then link from there to the mysterious pillars of cloud-fire that accompany the wilderness-wandering Israelites.

Is God’s creative work finished at the conclusion of the Genesis creation week? Though there is Sabbath Rest, this is NOT the end of creation- which may be a surprise. There is not merely one creation week, but many, punctuated by the sabbath that points to unrealised potentiality in God’s not yet creation. This is later revealed in the resurrection, which itself is not the conclusion to New Creation: which should perhaps have been obvious, but turns out to continue to be a well-kept secret. In all these steps we are led to the understanding that Creation is a many faceted living jewel, only the first flashing glimpses of which are portrayed on the first page of the Old Testament. The conceptuality of creation is emphatically not done with within the first few pages of the Good Book- I refute this entrenched error.

Just one of the principal means by which we are charged to speak God’s Word into being with God- our own voices giving faith-filled utterance to God’s thoughts is in the faithful preaching and witness of Good News to all persons. ‘…by all means possible, and if you have to, use words.‘ There must be words, for at the end, it is those who confess Christ as Lord that are saved.

Then follows a detailed analysis of the metaphor of the wine and wineskins in Mark 2, Matthew 9 and Luke 5. Unlike in modern brewing and fermentation techniques (with metal vessels and bottles and so on- though wooden kegs and barrels may also feature), the wineskin itself is changed by the process of maturation and creation of the wine. It is not possible to draw a hard and fast line of distinction between cause and effect, process and substrate; rather, both the skin and its contents are transformed. Importantly, the biochemical processes may be understood now, but they weren’t then: the mysteriousness of the process is part of the lesson and the claim. It is less a case of ‘Creation from new’ as it is ‘Creation from the old’, and ‘Creation in continuity’, with the partly understood action of yeast transferred from batch to batch. Furthermore, the identity of the wineskin is strongly indicated to be to do with the church within which we as individuals are brought to maturity, even as we bring maturing influences to others. The ekklesia of God is to be considered a co-creative agent as much as the individuals of which it is at any one time made up.

I conclude with a brief considerations of the areas of our individual and community life that might profit from a critical analysis and review in the light of this new understanding of creatio continua.

This post is the first attempt at what this fulsome review is that you are now reading, for the posts up to this point. I note in my ‘Introducing myself’ commentary I made the assertion that the dynamic of the ongoing agency of God with God’s people comes considerably- but only partly- through scripture/Revelation, and ALSO (which is why ‘partly’) by God’s Spirit. To spell it out: we are accompanied by the God who Speaks new things into being, especially if we will speak them with God. We are accompanied by the Life-breathing Spirit, if we are refilled with the same. We are being renamed by the Namer of Things, as we name and rename that which is remade, or made even for the first time, as we together prepare the New Creation. In the biological metaphor, as we have been gifted life, we are totipotent- and that full potentiality is achieved in the ideal environment, which is what God brings in God’s sovereign determining to co-create with God’s people, individually and corporately.

Joseph, the matured dream recounter-meditator-interpreter, filled and covered by the Spirit of God, co-broods with God over the chaotic Earth and its fragile inhabitants, to bring order and shalom. Above I spoke of the way in which we find our contribution is facilitated and our potential can be realised in the ‘environment’ that God oversees- this crucially includes the aspect of timing. This comes out more strongly to me as I consider my description of Joseph as a seed- a buried-in-the-dark germ of potential- his own awaiting the revealing of the sons of God. Like Esther trapped in the harem-‘palace’ for such a time as this. God is not approving of the muck under which we may be buried (God is not responsible for the moral ills that surround us, the as-yet unaddressed injustices we continue to practise upon one another; all the chaos of our globalised community), but the muckiness of the dirt and muck is no obstacle to the sovereign upheavals that God orchestrates. He is, after all, the God Who raises the dead.

No surprises there- well, there shouldn’t be.

Then again, yes there should be surprises, for the General Resurrection is to be but the first Step into the consummated New Creation, when God’s creation project moves to the next stage that we can behold from this present vantage point. And what we shall be has not yet been made known. What we do know is that we shall be delighted to be glorified with the Glorious Christ, hidden safely within the Revealer of God’s secret future.

It is in the climax of Genesis in the lengthy account of the sons of Jacob, Joseph and his brothers, all separated for so long, but then reunited because God intended it for good that I see the cosmic scale and the human-with-God scale of Genesis combined and brought to climax-resolution. In the opening lines we receive a beautiful depiction of the works of our beautiful God, who makes things and makes those things to make themselves. God’s perfection is sovereign over the allusions to imperfection admitted in references to ancient myths (of chaos and the like) and the mystery of theodicy. We now understand better what the original readers only guessed at in their star gazing- the huge scale of the solar system and galaxies in which we are placed, separated by so much space. Yet they are brought together in Joseph’s dream, as figures of his family, temporarily separated and parted across a great gulf, before finally being dramatically and truly reunited. The dream of co-creation that Adam and Eve fall short of is realised in the family of Jacob, and most particularly in the life mission of Joseph, who stands as an example for all who follow.

On the follow up (‘Interpreting troubled times’) I explored the proposition of Open Theism, in which God has not decreed or predetermined the details of our presents and immediate futures, but rather empowers our agency, individually and thus corporately, under the ultimate sovereignty of the Divine. Our agency is, I assert, in fact commissioned, charged and gifted to us at a largely-as-yet-unrealised scale amongst the collective peoples of God, distributed across a multitude of divided denominations. My assertion is that our situation is much more charged with possibility and potential than we have been schooled to embrace. My assertion is that we should be following Joseph’s example of preparation and readiness much more seriously and energetically than we have been schooled to embrace. We have been encouraged to work out our salvation with fear and trembling, but not so much to engage in the marketplace business of managing the world in which we find ourselves, the creation under our continuing stewardship that is in fact much more at our disposal than we have accepted (and certainly much less under the sway of real but mysterious agents opposed to the kingdom rule of God, revealed gloriously in the victorious Christ). Ultimately we do well to admit that God is more in control of eternal destinies than we are, but we have neglected responsibility for the upkeep of the House in which we now live and have our being, for which we will find ourselves principally accountable.

I concluded in this manner: “To put it as my manifesto: God wants us to create the future with Him. Right now, the nations are looking for Joseph-like image-of-God-like overseers. Who will they find? Will you get ready? For us as for Joseph the young dreamer: God’s creation is waiting for us.”

Obadiah (1 Kings 18) is an example of a man who lives in reality, at the collision of the categories of life in our minds and hearts; the tectonic plates of the secular and the spiritual: the meeting of the ideal and the pragmatic, the life in the now of chaos, crisis, of living as a person of character and principle in the face of crisis and triviality, under the crush of oppression and despotic leadership. Obadiah is not a man who endures with faithfulness, so much as that with God and with God’s prophetic people he acts with significant agency. He does not hold all the cards, he does not have his hands on many of the levers of power. Yet through his significant individual service under God, righteousness prevails, and he is finally seen as one who moves forward the Economy of God (God’s Kingdom, we might say) against and over the economies of humankind, of whatever forms. In that triumph we realise that the sacred and the secular were never to be seen as separate- that perhaps is a sin that the co-creator manifesto stands to refute.

With my friends in Kenya, I reflect that the investment that we make in great temples should be into the corporate Temple of the ekklesia, and its living expression in the community. Everything rises and falls on leadership, opined a wise friend of mine, and so we best invest in making more co-creators who will live and lead at the meeting point of heaven and earth.

Wineskins were known to be in organic connection with the wine produced in them, in a manner fundamentally at odds with the scientific method, in which the choice of materials for laboratory glassware is such that the possibility of reaction with the container itself is (almost certainly) excluded. The fact that the parable delves in detail into this procedure that would be immediately refused by the lab scientist is growingly instructive. Genesis (1-11…) is polemic refutation, I observe, and so it is also a warning against independent human sense-making. What emphasises the ‘You’re not going to understand this in a rational sense’ mode of Genesis 1 is, for example, how the spoken word of God is portrayed as the immediate cause of light, which we know “in fact” has its natural origin in various phenomena of luminosity- which is exactly what the opening passage goes on to admit- the later creation of non-deities of sun, moon and other luminescent objects in the upper heavens.

Just as God’s words of judgement over man, woman and serpent are also creative, so also are Moses’ judgements uttered over the gods of Egypt; they are all means to the restraint of evil and creation of a new life into freedom, however long those journeys may prove to be.

How do we understand the seventh day of resting, from Genesis, and the Sabbath day, in Exodus? Are we bluntly instructed to sit/ stand around and simply sing in the dark, loitering ‘worshipfully’ in this cosmic waiting room for the main event to follow- ie mostly a passive process of patience and preaching to choirs? Or might we learn different lessons from the strange gift of the shared Resting of the Divine- a reorientation to this world of stuff and things? I think the sabbath ties us together with the substance of our reality in a relationship that invites a more transcendent dynamic than that of mere creatures. Our doings are then to be shaped by the invisible order of heaven, by our living relationship with the creator of what we are becoming as well as of what we are. Or directly as our Lord Jesus put it- not so much rule keeping or habit maintaining (though they have their uses) but watching Father, and doing what He is still doing- being about our Father’s business. That is going to be making New, not merely sorting out the stuff in the garage for lack of anything else to do.

Just as God is free and unconstrained in Creation in the beginning, creating the universe out of free love, not out of any obligation, or within any bounds of necessity, so too are God’s called and gifted co-creators. “I’m leaving you in my Garden to till and watch; I’ll see you this evening and you can show me around.”

God sets up the possibility of unity between God and humankind at Gen 22; Moses enacts the making of the Body to which God as Head will be joined; the greatest act of co-creation.

Godself, the Incarnate God in Christ is the true answer to Platonism. We are led and accompanied from our bind; we are gifted a good life in a good world rather than abandoned as fools in a false fold; the transcendent God who is Unlike us nevertheless takes the form of flesh to sympathise-empathise with us in our weakness, to unite with us in our trials and thus to re-gift us the call to co-creativity and co-creation. {We can explore the bounds of this for the (Not-Yet) believers.}

The locus of co-creation moves from individuals (each equivalent to Josephs) to the Church Age ekklesia, and therefore at a scale fit for the challenges that we face. Nevertheless, the unit of agency is still* the individual, best in hupotasso partnership with God. Both ends of the scale are important: ‘each one reach one’ is the key dynamic for evangelism, while the Church in unity speaks (through actions as well as words) to the concerns of society and planet. Joseph, Daniel and the like do not broker what we might today call spiritual revival; they are portrayed as witnesses in the elite marketplace, with an emphasis on character examples at the level of national leadership.

The LORD, Sarah and Abraham: A study in Encounter.

Genesis is the account-theological history-polemic sandbox-manifesto of God’s dealings with God’s creation, especially God’s people- and that means all of them, all human beings, though the scripture opens our understanding to some of them in particular. In Genesis 18 we are given insight into God’s deliberate concern with His chosen couple, Abraham and Sarah, as there is an encounter between Theophany and the first pair of the new covenant that will become their grandson Israel-Jacob. This encounter is a more fruitful one than that in the first Garden, where God’s Word was rejected outright by the woman (Gen 3:6 and also her husband!). In this case, human freedom, by which I mean Sarah’s agency, is respected, and thus she is drawn into the fruitful purpose of God, which leads soon enough to conception and pregnancy- the child of Promise!

Encouraged perhaps by this surprising turn of events, in which Abraham no doubt notes that his wife’s test of faith is accepted gracefully by the Lord and diffused in a redirection of promise and purpose- God too passes this test (!): Abraham then continues in the same manner. Once the woman was asked, ‘Did God say..?’ and when all the doubting and disobedience was done, God defers the day of judgement. Now the day has come for God to judge Sodom for its persistent, deliberate and studied wickedness- or has it? In this landmark and seminal encounter between the human creature and his God, both agents are portrayed as – dare I say it?- equals. God is still God, and the man his creature formed from dust (and he knows it), but – and this sounds ridiculous, and it would be ridiculous, if it wasn’t in holy writ- God and His man constructively get in each other’s way. At the end, God is still the One who goes on to make the final analysis and ultimate decisions about judgement, but it seems (as the narrative focus shifts back from Sarah to her husband) that Abraham has been elevated to a position not much dissimilar to that of the heavenly council that is repeatedly alluded to in the text of the Hebrew Bible. Now here is what is important: this sort of apparently heretical reordering of the hierarchy and dynamics between God and creature is a polemic-narrative formulation delicately embraced in order to make a more fundamental point about God’s intention for the type of relationship we all have with Godself. The scope of this relationship, says the scriptural text, potentially breaks out of the boundaries of the natural order of things. The facts of life are sound and our trust in them is well grounded- today we now know the processes and limits of reproduction, of longevity and the likely cause and effect processes that will lead to our mortal demise. We are delicately functioning creatures existing more or less comfortably within the checks and balances of our very delicate biosphere, today manipulated to our benefit by science and technology. Within this understanding, fertility is a phase, menopause is a fixed reality, and so is our aging and death. We are creatures whose lives are underpinned and bounded by the non-negotiable of time. In the last decade new leaps in medical technologies keep pressing at and manipulating the thresholds of these phenomena- fertility treatments, premature birth or abortion, life-saving technologies even including gene therapies, transplants and chemotherapy- but my newspaper now tells me that the long trend of increase in life expectancy is tailing off, in the UK and globally. All of this current commentary is anachronistic to Genesis 18, and that doesn’t matter at all, because Genesis 18 puts all human creatureliness into a box and God says, ‘I have something larger in mind for us.’

Once fertility is gone, we can’t do anything about it. But God arrives outside Sarah’s tent to say that the Creator of New Life is here to make promises and deliver on them- to make new life with humanity by means that transcend biology. This miracle is made to look like a fluke pregnancy long after menopause, but God might as well have put Sarah to sleep and taken a rib from which to make Isaac- its pretty much the same thing. What God is prepared to make us partners in with Godself is integrated with our biology, with our enfleshed natures, but already transcendent to it. Flesh and Spirit giving birth simultaneously, synergistically.

And as the Three Visitors meld into One, and makes to continue on God’s Way to Sodom, the same dynamic is offered to Abraham- God’s putative co-creator partner. Here in Genesis, well before there is any notion of the final judgement and the hereafter, of any sense of our existence (or lack of it) after our death, there is the frank recognition that the life of human beings is limited. Through the genealogies there is the clear admission that we are born, we live and (possibly) reproduce, and then we die. But God is not speaking in Gen 18 about this natural order of things; rather, there is a moral situation to be evaluated. There are non-biological criteria for life. And these are not mysterious laws operating in an unseen realm beyond our ken. They could be, but God says they won’t be hidden from us. He draws Abraham within this veil. God is going to apply different criteria to the question of when the bounds of our mortal lives are reached, and what is more, God is sharing agency with us. We didn’t know this: God says He is going to tell Abraham what He is up to, and then, without being asked, Abraham initiates- he responds- the relationship becomes reflexive; consciously, deliberately, agentially. Of course, when I say without being asked, I take it that you understand that God is offering this possibility. Co-creation is not hubris or heresy, purely because it is God who is advancing this hypothesis. Is it possible for My human creatures to partner with Me in creating the future? I hope so- let’s find out! (Else freedom is a deceptive ideal shrouding the Hobbesian reality- life ‘nasty, brutish and short.’)